In 2016 I wrote a thesis for my BA in Photography titled:

The Poetics and the Politics of Imagery:

National Geographic's representation of place through Instagram.

I've decided to revisit my thesis as it was something I enjoyed working on at the time. Some of my opinions might have stayed the same, and on other things I've definitely changed, so it's been really interesting to share what I wrote then. First, there was the Introduction. Then there was Chapter One: the Poetics, and Chapter Two: the Politics. This is Chapter Three: The Imaginary.

Imagined Geographies

‘Imagined geographies’, the item of discussion in Joan Schwartz and James Ryan’s book Picturing Place[1], evolved from the writings of Edward Said and his work on Orientalism. The term ‘imagined geographies’ refers not to something that is made-up, but is about perception. In a more specific relationship to photography, it is about how space and place is perceived through images.[2]

In the introduction to Picturing Place, the power of the photograph is highlighted in relation to the progression of transport at the time of photography’s inception; “Thus, at a time when steamships, railways and the telegraph made the world physically more accessible, photographs made it visually and conceptually more accessible.”[3] The theory implies that it is less about the view of far off countries that people were given, but how this view was a very selected representation of this ‘new world’. While travel writing had strived to describe unknown landscapes, once the production of the photographic image commenced it became an almost void mode of representation. Joan Schwartz in her text The Geography Lesson draws upon the writings of Antoine Claudet to describe how photography changed the culture surrounding the viewing of other places. Schwartz quotes that photography gave life to the “historical records of former and lost civilizations; the genius, taste and power of past ages, with which we have become familiarized as if we have visited them,” and that reiterates the last phrase in italics in order to overtly highlight how the language being used to discuss photography was clearly publicizing the medium as truth; ‘As if we had visited them’.[4] Photography was seen as a pure representation and a champion for positivist science. By keeping visual representations of these unknown countries to within a set number of socially accepted and expected ideals, it made these places conceptually easier for the viewer to approach. This point is made clearly by Ryan and Schwartz:

“Initial emphasis on the realism and truthfulness of photography effectively masked the subjectivity inherent in the decision of what to record, from what angle and when … and likewise veiled the power of photography to mediate the human encounter with people and place.” [5]

When images are produced to reflect social expectations and aesthetics, the results can be found containing very little investigation of the place photographed. When formulas such as ‘the rule of thirds’ exist for aiding in composition (with many modern cameras coming with the options of screen grids for better reference) the photographs made can be seen as simple reiterations of previous work and generations.[6]

Since the production of the photographic image began, specifically the making of exploration photography, aspects of the imagined geographies of these far off landscapes has shifted in relation to who or what is the focus of the image. Photographic practices still capture images of the landscape and ethnic peoples, and Schwartz’s view of the photograph being seen as “not merely … visual reflections of the ‘real’ world, or solely of the intentions of their maker, but as discrete moments in the production and circulation of cultural meaning, which call into play a range of processes, spaces, actors and audiences,”[7] still applies. The major change in photographs taken today is the change in cultural meanings, something that is expected and anticipated with time; and the space the image is viewed in has become digital media, the audience therefore limitless.

(fig. 3.1) Randy Olson. ‘Writer on Phone’.[8]

When large corporations like National Geographic produce images of people they champion as explorers in different parts of the world, the image, while still referring to the ‘otherness’ of the native people, is no longer the reason the audience consumes the photograph. It has now become almost exclusively about the explorer, about the westerners building an image of themselves that is exciting, attractive, morally pleasing, etc. The surroundings become nothing more than an interchangeable backdrop. From this our gaze should shift to “the roles of photography in making ‘imaginative geographies’” and how this “involves blurring the distinction between the real and the imagined.”[9]

In (fig 3.1), the image is focused on the white western man working on his iPhone. The mixture of his tousled hair, dark dirt-coloured clothing, unshaven facial hair and level of assumed physical fitness all fit within the current perception of an ‘explorer’. The man pictured is a writer for National Geographic. The accompanying text is written by the photographer he was working with at the time and goes into great detail about the relationship between the two of them.

The location of the image and the identity of children surrounding him are only alluded to in the closing sentences of the accompanying text. The text and imagery can both be read as works of self-promotion; being told in a storybook style of the time and space travelled though together immerses you in their lives. The landscape is not important but rather the idea of these men willingly spending their time there, a place that one assumes will result in an uncomfortable lifestyle (as the image implies it is not as developed a country as their own).

While it is true that “we have interpreted the geographical imagination to be the mechanism by which people come to know the world and situate themselves in space and time,”[10] the imagined space no longer has a specific place. The imagery is not taken to document the native people but to document the Westerner’s experience there. The landscape within (fig 3.1) is interchangeable with the majority of other developing countries in Africa. It holds the tropes that are associated with such locations: ethnic settlements, rural setting, and non-western looking people. It is the western writer that the viewer is directed to have the association with and form a connection to.

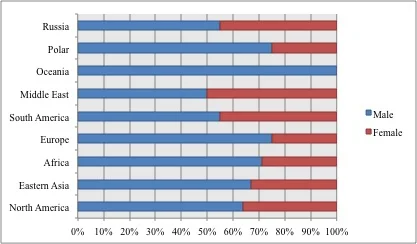

Elizabeth Edward uses (fig 3.2) for the cover of Photography and Anthropology 1860 – 1920.[11] In work I have read surrounding this photo, parallels are drawn between it and a zoo – the young girl standing separated from the black males in their ethnic dress as if there is a fence between them. The image holds a strange balance of power: the child seems unthreatened by the men standing in front of her like a display. Likewise the men seem to be waiting as if they were captured wild animals.[12] Although there is a strange relationship being shown in the image, there is a gaze directed towards the males, even if it is the view of the terrible ‘lesser’ people. In comparison to (fig. 3.1), where the role of the native people is merely background material to raise the social standing of the writer, there is a visible shift in interest.

(Rereading this now, I find it uncomfortable, as I feel like I didn’t quite know enough to write about race in 2016.)

(fig 3.2) “S. Andamans,” 1911. Photograph by H.W. Seton-Karr, Royal Anthropological Institute of England and Whales.

The writings of Judith Donath in Communities in Cyberspace[13], although composed in the late 1990s, alluded to the importance of such characteristics as identity and connection in online social society, and are applicable to imagery today. In her essay, Donath writes about the idea of online identity and deception in virtual communities. She foregrounds the work by lying out some basic differences between the idea of identity in reality and identity online. In reality normally one can say there is one body and therefore one identity. The existence of multiple online social platforms results in people creating a range of new social spaces, each of which can be created around a different persona of the same body. Because there is such possibility for deception online, assessing whether information is trustworthy or not brings about a search for something that proves identity and credibility; therefore “identity is essential.”[14] The rational that identity and ‘truthfulness’ are interlinked is both aided by and further binds the link between photographic representation and ‘truth’. It is this that blurs the line between fact and fiction on photo-sharing platforms such as Instagram. From this point it is clear why the story about the relationship between the photographer and writer of (fig. 3.1) relevant. “No matter now brilliant the posting, there is no gain in reputation if the readers are oblivious to who the author is.”[15] It is this need for connection between the viewer and the identity of the individual behind the information that has lead to this shift in vision.

To further the idea of a connection between National Geographic and their audience, they have created their own online community for people to submit imagery to. The community, ‘Your Shot’, has the welcoming blurb of: “Welcome to Your Shot, National Geographic's photo community. Our mission is to tell stories collaboratively through big, bold photography and expert curation. Get started and show us your best!”[16] The publicity of their community builds on viewer’s aspirations to be create content ‘worthy’ of their brand, offering the chance for members to have their work assessed by their editors and professional photographers.[17] The imagery that is submitted to their community results in people mimicking their style of photography to achieve esteem.

The uploading of imagery to multiple virtual spheres brings about a loss in ownership and control on the image. When the distribution of an image was restricted to physical mediums there was the possibility of destruction or loss of the photograph. Once again, with the advent of digital dispersion the power of photography has changed. To quote Schwartz and Ryan, “The same images, now preserved across a range of social spaces … continue to influence our notion of space and place, landscape and identity, history and memory.”[18]

(fig. 3.3) Ciril Jazbec. ‘Migrant Child.’[19]

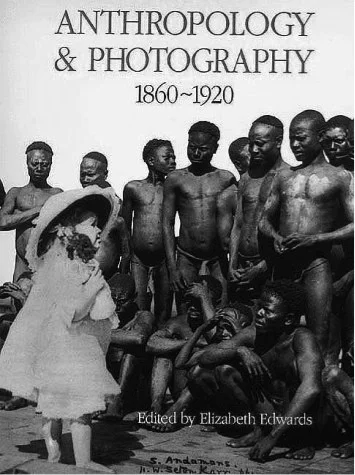

On online social platforms, the photos that one uploads form a timeline and represents specific views to the audience. When viewed one after another, the imagery displayed forms representations of either people or places or ideas. When conducting my content analysis on National Geographic’s Instagram account, I noticed that there was almost no imagery of violence or war. (Fig. 3.3) is National Geographic’s only representation on this social media outlet of the current crisis regarding Syrian refugees.[20] Depicting a child under what is assumed to be the yellow tint of artificial light at night, the photo was made at the standing height of the child, conveying feelings of overcrowding and stress. The expression on the face of the child is at a minimum blank and tired, while in my interpretation expressing emotions of confusion, loss and extreme exhaustion. Without reading the text, it is impossible to tell the gender of the child in this image. The combination of large eyes and lips with no visible facial blemishes places the child in a gender-neutral bracket. The child becomes an easy person to relate to when there is no gender restriction for the viewer to be influenced by. The gender neutrality of the boy could be seen as an appropriation of the cherub child and their angelic characteristics. The child, while being a refugee, can also be aesthetically pleasing for the viewer, possibly making it easier for the audience to form a momentary connection to the child.

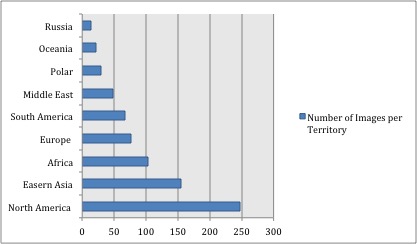

To add to this consideration is the result on gender representation from my content analysis. In the content analysis, the Middle East and Russia were the only land areas to have at least an equal or higher representation of women than men. The relationships between the United States and both territories have contained a strained nature since 1945.[21] With a higher representation of women and no major acts of violence shown (that were not part of a cultural or ethnic ritual), the countries within these areas receive a new image. National Geographic is a company based in the United States, and the representations of these areas could be assumed to be part of an emasculation[22] process. Similarly to (fig. 3.1) these countries often act as an interchangeable backdrop with specific geographical locations not given, and therefore become an imagined landscape the viewer can edit.

It is not just the images created by companies such as National Geographic that hold an imagined geography, but also the images that viewers then propagate of themselves. The creation of their online identity is now centered around photographic practices, playing “a central role in constituting and sustaining, both individual and collective notions of landscape and identity.”[23] With ambitions of gaining higher popularity users will recreate imagery in the style of those they admire or feel they should aesthetically copy. Donath reiterates this point, writing that throughout the multiple social platforms, “Though the rules of conduct are different, the ultimate effect is the same: reputation is enhanced by contributing remarks of the type admired by the group.”[24]

New projects using Instagram as a platform have taken the theme of identity a step further. During August of last year (2015), an Instagram account belonging to a Senegalese migrant embarking on an illegal journey into Spain became viral after receiving coverage from large reporting houses. It was revealed then that the account and imagery featured on it were part of a campaign to promote the international photography festival in Getxo, Spain. The festival organisers hired a team to produce promotional photographs and videos, while at the same time raising questions about the use of photography in modern society.

(fig. 3.4) Image of the ‘migrant’ Diouf [25]

All the images on the account were self-portraits made by the ‘migrant’ Diouf, with each image showing different stages of his journey to Spain. In an interview for Time, the organisers of the festival stated that the fake account was a way to show how the “narration of reality is always in the hands of people with power, not in the hands of people living that reality.”[26] It is such statements that echo the shift of view of non-Western countries, and relates back to one of the opening quotes from Schwartz and Ryan:

“Initial emphasis on the realism and truthfulness of photography effectively masked the subjectivity inherent in the decision of what to record, from what angle and when … and likewise veiled the power of photography to mediate the human encounter with people and place.”[27]

Images today remain tied into the same trap of only representing social expectations and approved aesthetics. We now consume photographs that are created to give us an instantaneous connection to a person that is easily relatable to, or to enable the spread of images containing the view of the world that we approve of and then mimic.

Footnotes

[1] Schwartz, Joan, and James Ryan, eds. Picturing Place: Photography and the Geographical Imagination (international Library of Human Geography). London: I. B.Tauris & Company, 19 Apr. 2003

[2] When looking back to the landscapes from the Darwin article that was analysed as part of chapter one, there is a very definite tone and perception to the reading of these images. The imagined geography of what we assume to be a representation of the Galapagos Islands instills ideas of abandoned spaces and untouched wilderness.

[3] Ibid. p. 2.

[4] Cit. Op. Schwartz, 1996. p. 20.

Quoting: Claudet, Antoine. ‘Photography in its Relation to the Fine Arts’, The Photographic Journal, Vol. VI (15/06/1860), quoted in Gernsheim, The Rise of Photography 1850 – 1880, 66.

[5] In the introduction to Picturing Place, Schwartz and Ryan open by writing about how one of the major trends of the Victorian Era was to categorise and collect – and how the advent of photography in such an era heavily influenced how it would develop as a medium. Cit. Op. Schwarts and Ryan p. 3.

[6] Maria Antonella Pelizzai refers to tourist photography (and photography produced for tourists) as a ‘homogenous production’, indicating to the lack of creativity or unusual imagery that one would find in tourist photo albums. Ibid. p. 56.

[7] Ibid. p. 8.

[8] Accompanying text:

photo by @randyolson | I’ve spent more time with @neilshea13 in Africa than any other writer IN MY LIFE. Many photographers for @natgeo are almost most of the time working in far off places. But Neil and I have worked through the top od the Omo River in Ethiopia to the bottom of Lake Turkana over the last many years – walking into the same villages, travelling in the same car and staying in the same camps. I have great admiration for him and his visual writing. Maybe I can convince Neil to post some scans of his notebooks so you will understand how he works … he draws everything ... he approached situations like a documentary photographer ... sitting back watching the scene unfold and taking it in … burning the visual into his brain so he can write about it later … sketching away in his notebook and being and ambassador for all of us as I do my “Cyclops” thing (his words about how photographers are mono-maniacal). And just recently he has entered our photography world with a documentary on Kakuma Refugee Camp. He is off soon for another story, on refugees and I will continue to post Lake Turkana photos here in the hopes that the people we met will still have a place to live after the Ethiopian dam on the Omo river goes online. In the hopes that they will not be the next wave of refugees.

You can see our project archived at #NGwaterstories, which is linked to our feature on Kenya’s Lake Turkana in the August 2015 issue of @natgeo magazine. Join us @randyolson and @neilshea13 as we follow water down the desert.

[9] Ibid. p. 6.

[10] Cit. Op. Schwartz and Ryan. p. 6.

[11] Edwards, Elizabeth, ed. Anthropology and Photography, 1860 – 1920. New Haven, CT: the Royal Anthropological Institute, London, 1994.

[12] Keeping in mind what Elizabeth Edwards wrote in her introduction, it is hard to analyse images from other historical periods and not apply possibly misleading contemporary views upon them:

‘New and very different cultural and epistemological contexts make it impossible, of course, to view the material with the same conviction with which it was viewed by contemporaries.’

Cit. Op. Edwards. p. 3.

[13] Smith, Marc A., and Peter Kollock, eds. Communities in Cyberspace. London: Routledge, 1999. Print.

[14] Ibid. p. 29.

[15] Ibid. p. 31.

[16] National Geographic Your Shot (2015)

Available at: http://yourshot.nationalgeographic.com/about/ (Accessed: 8 January 2016).

[17] Competitions are held on the site, but are renamed ‘assignments’ or ‘stories’. This rebranding gives the user a feeling of inclusion within the NatGeo brand, and possibly more motivation or purpose to their image making. While the style of photography that National Geographic propagates is further copied and revered.

[18] Cit. Op. Schwartz and Ryan. p. 6.

[19] Accompanying text:

Photo by @ciriljazbec / Last night I entered the temporary transit camp Opatovac on the Croatian-Serbian border. There was a group of people waiting for a bus to take them t the Croatian-Hungarian border. It was a cold night and some people were wearing blankets, and this boy looked up at me as he waited patiently with his father. Follow more at @ciriljazbec and @natgeo #refugeecrisis #migrantcrisis

[20] As of 01/01/16.

[21] In regards to the Middle East, the United States has been involved in a ‘counter-terrorism’ military campaign with several areas within the Middle East, stemming from the end of World War II. There has been a marked increase in their efforts after the 9/11 attacks on the twin towers.

Russia and the United States were the key figures in The Cold War, a time of political and military tension after World War II. Since the cold war relations have remained tense.

[22] Derived from from Latin emasculat- ‘castrated’, from the verb emasculare, from e-(variant of ex-, expressing a change of state) + masculus ‘male’. Therefore, to make someone/something weaker or less effective from the idea of making more feminine.

[23] Cit. Op. Schwartz and Ryan p. 6.

[24] Cit. Op. Smith and Kollock p. 31.

[25] Accompanying text:

The superbike for the first stage. I don't know what will waiting for. Problems tears and cold but now im positive my friend hagi take me to nouadhibou. #ontheroad#travelgram#jujuy#nicetime#discover#explore#instagood#instadaily#exploremore#backpackers#adventure

[26] Laurent, Olivier. Creators of fake Instagram account showing a migrant’s journey speak out. TIME.com, 3 Aug. 2015. Web.

Available at: http://time.com/3982506/immigrant-instagram-migrant-journey-abdou-diouf/. (Accessed: 8 January 2016).

[27] Cit. Op. Schwartz and Ryan. p. 3.

![(fig. 3.1) Randy Olson. ‘Writer on Phone’.[8]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53340653e4b0943ce189926c/1523802229836-XRBWFTIJ9PINER27STE3/Thesis_chpt3_001.jpg)

![(fig. 3.3) Ciril Jazbec. ‘Migrant Child.’[19]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53340653e4b0943ce189926c/1523802651385-2MD1JSLNHX3EZEJUW8FF/Thesis_chpt3_003.jpg)

![(fig. 3.4) Image of the ‘migrant’ Diouf [25]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53340653e4b0943ce189926c/1523802688991-LXMGO6WAXH3SIWNXMCWO/Thesis_chpt3_004.jpg)

![(fig. 2.2) Ami Vitale, ‘Protecting the last male white rhino’[29] shown on the National Geographic instagram account.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53340653e4b0943ce189926c/1523801601321-HI2L3WUD48BNASZMDGW1/Thesis_chpt2_002.jpg)