This number game started a few months ago.

I'd moved back to Dublin after fracturing my foot while walking 4,000km around Ireland, and was delaying finding another part time job as, well I couldn't really walk for starters, but I also kind of just wanted to "try being an artist" for a while. With almost no money, and limited mobility I was struggling to leave my room and feel creative. Any creative sparks I did encounter I would quickly blow out in my hasty rush to catch them, my flailing, snatching hands overwhelming these fleeting moments and ultimately extinguishing them.

The walking project wasn't finished, and after many physio sessions we set a date to return to life on the road. I made a wall calendar to count down the days, and counted them out.

90 days.

Such a satisfying round number. What could I try to do for 90 days?

The year before I'd put out an open call for people to send me words, the theory being that I would send them an image in return. Final year college plans changed, and I just put this project in a folder on a hard drive and mostly forgot about it (it's only purpose to make me feel guilty every so often for never getting back to it).

If I just started making images and posting them somewhere, no one else would know what I was working toward, or was possibly going to happen in 90 days. I went through the images that I'd started making for the project in the beginning and picked out the ones I liked. It was enough to give me some time to shoot some more images - I'd decided to shoot film, just because I enjoyed it.

The "somewhere" to post was also pretty easy for me to decide; I'd created a second instagram account for my "Photography", so that I could use my regular one for just posting videos of me messing around in the climbing gym. In reality I'd just ended up with two out of sync accounts, so decided I might as well put one of them to use!

I received 40-odd words for original project so I knew that I'd be posting a mix of old, new, related and random. I found it really enjoyable to slowly wade through old hard drives and find stuff I'd shot previously while at the same time make new photographs - I got to see some developments/shifts. In the end it took me over the 90 days to publish all the photos, but they're now all out there on that instagram account, if you're interested in the full 90.

One of the only struggles I had with this project was remembering that this was just to be fun, and not to worry about there being any deeper meaning. I am allowed to create work for fun, and when I do it gives me the breather to look at bigger topics with fresh eyes. But now I'm meandering, so let's get to a point.

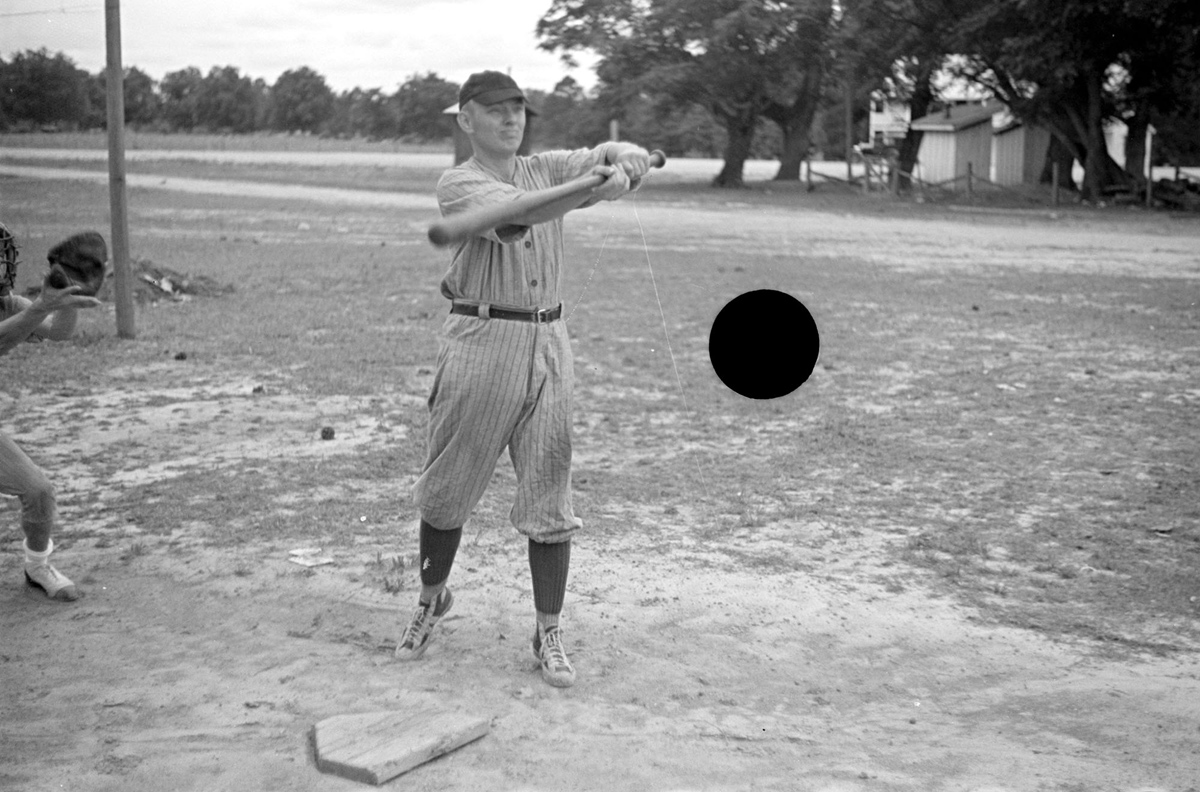

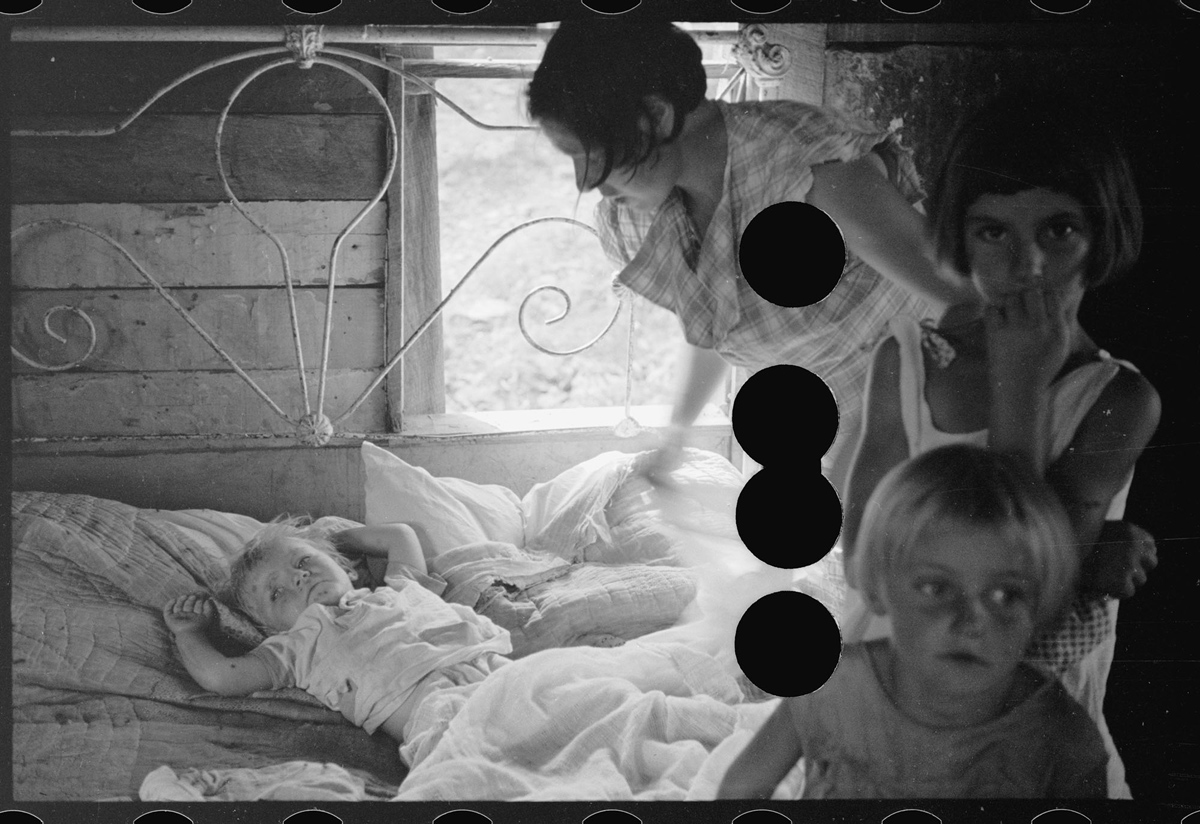

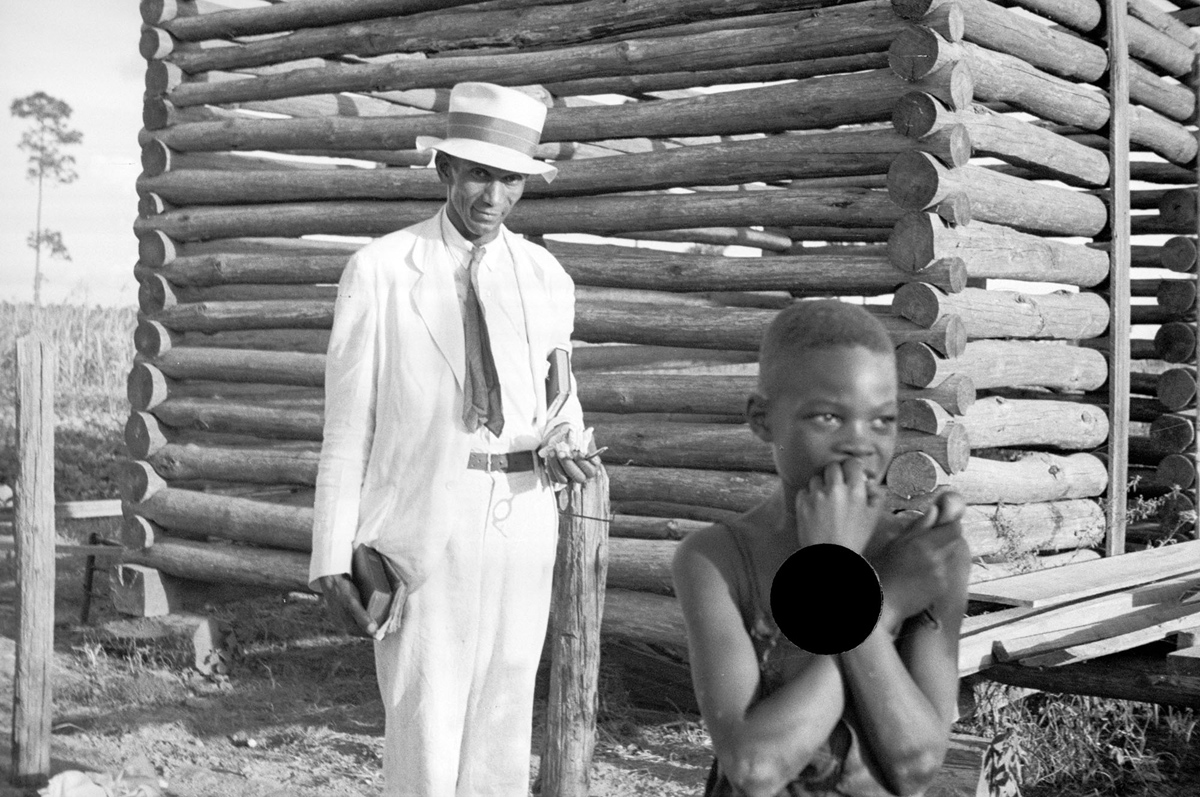

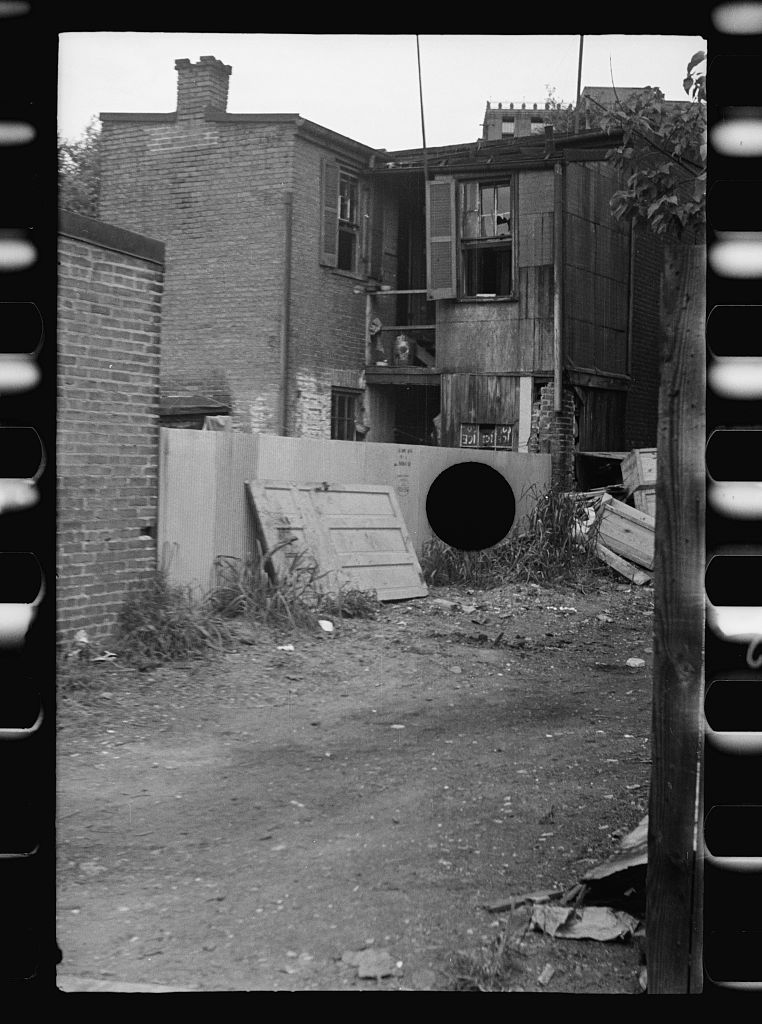

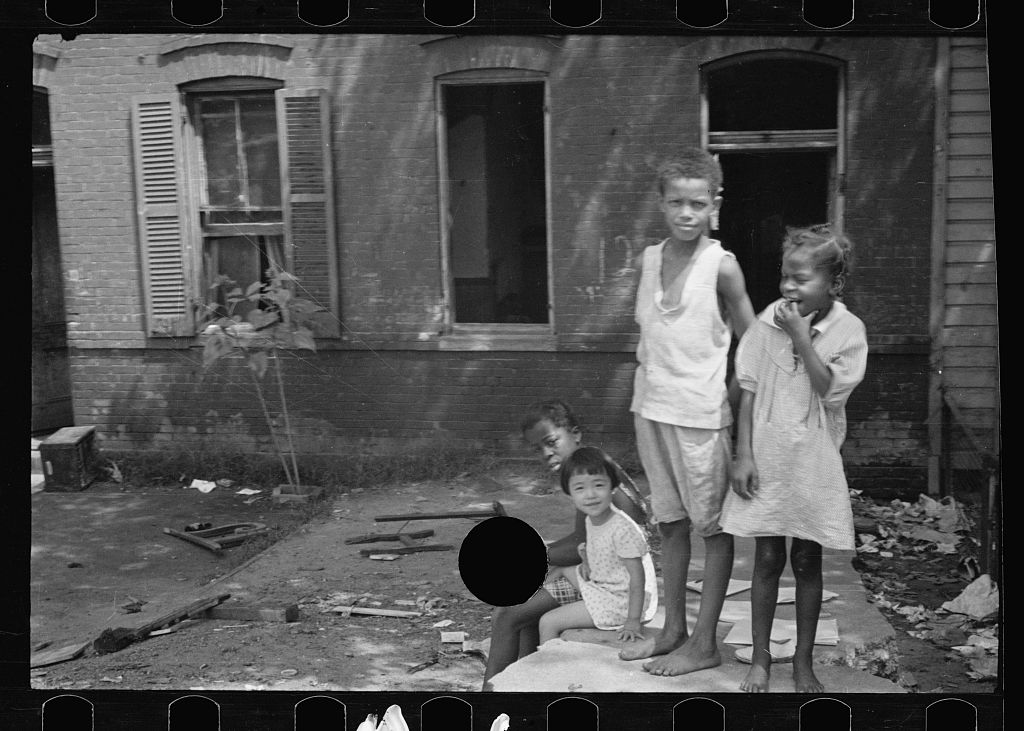

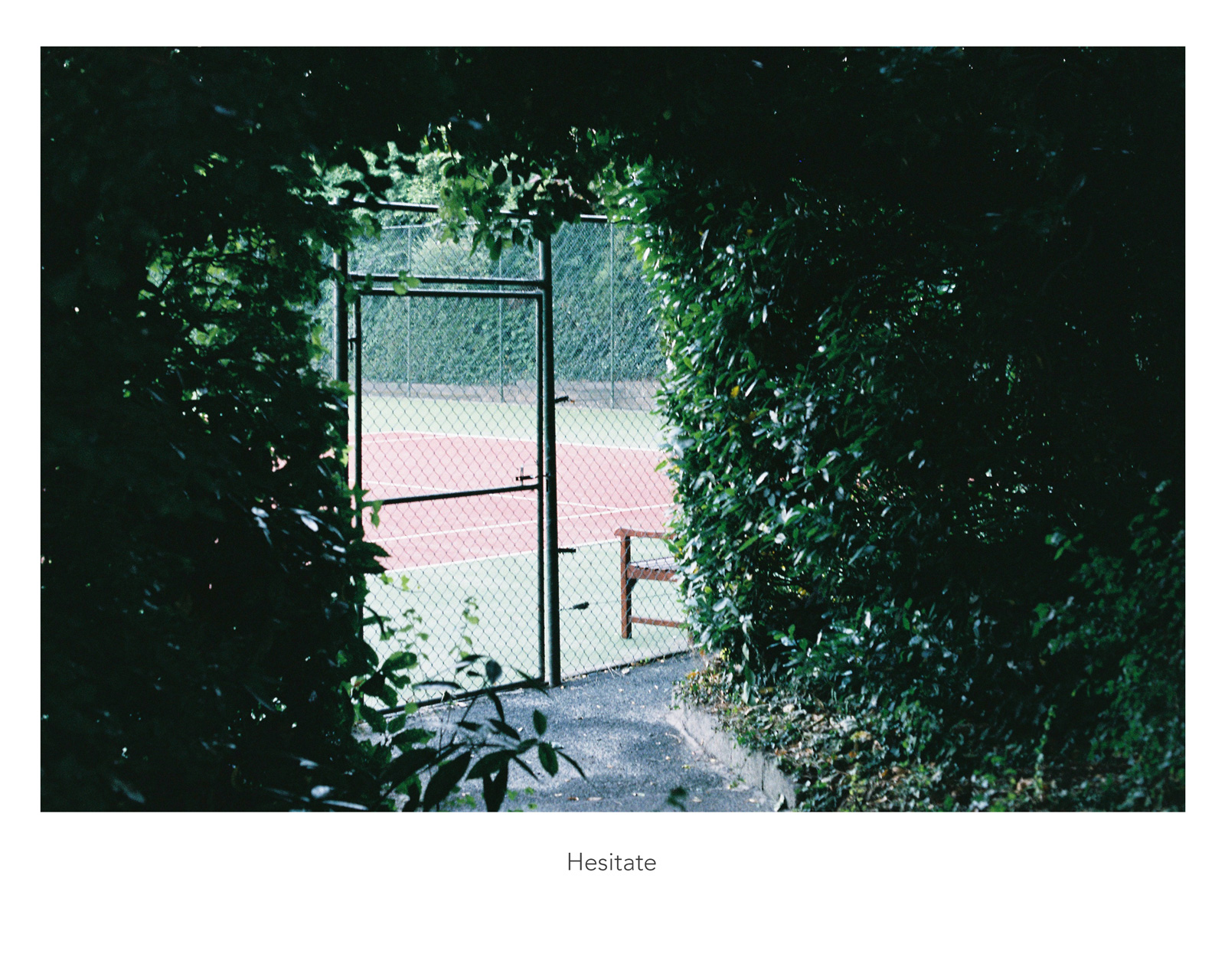

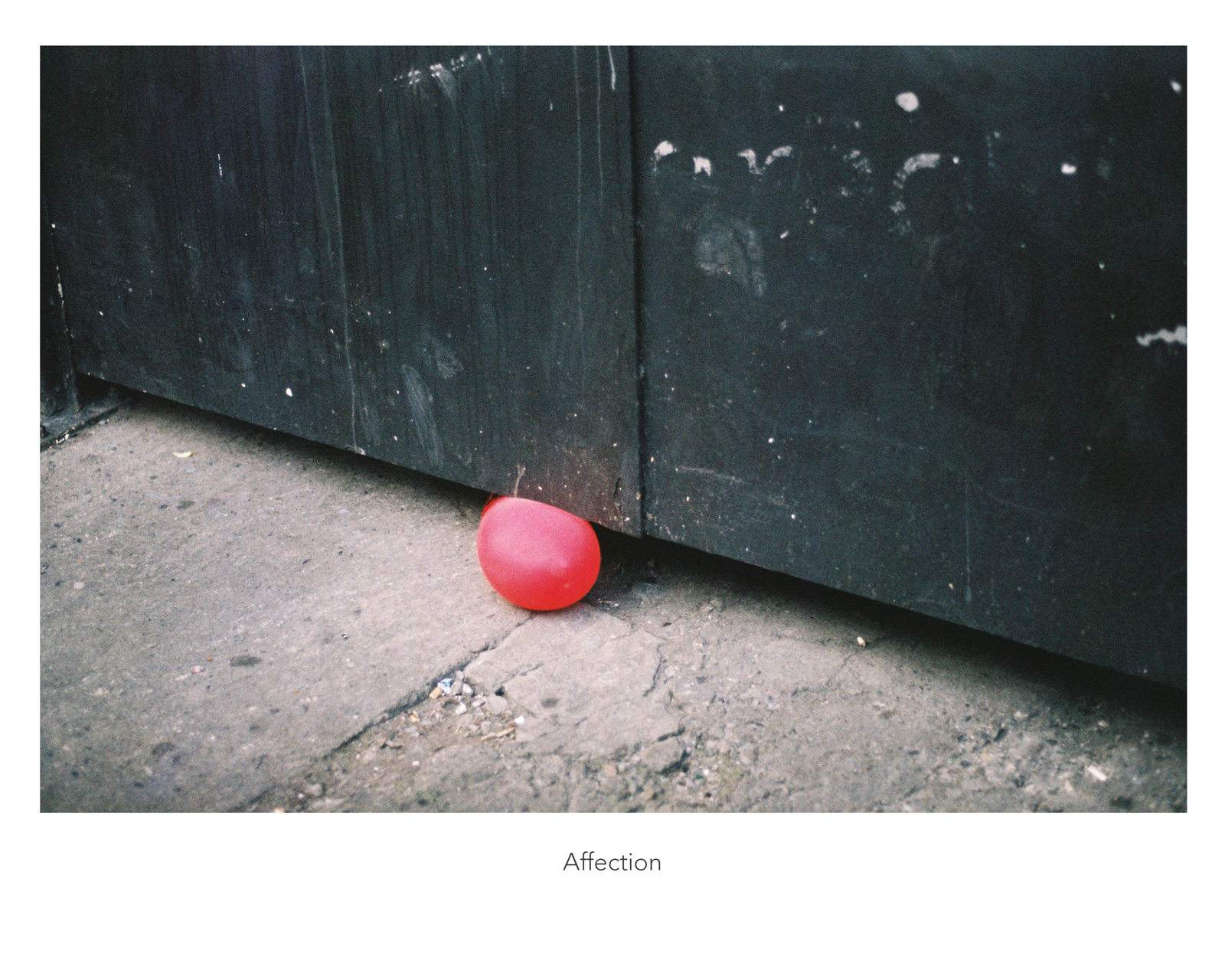

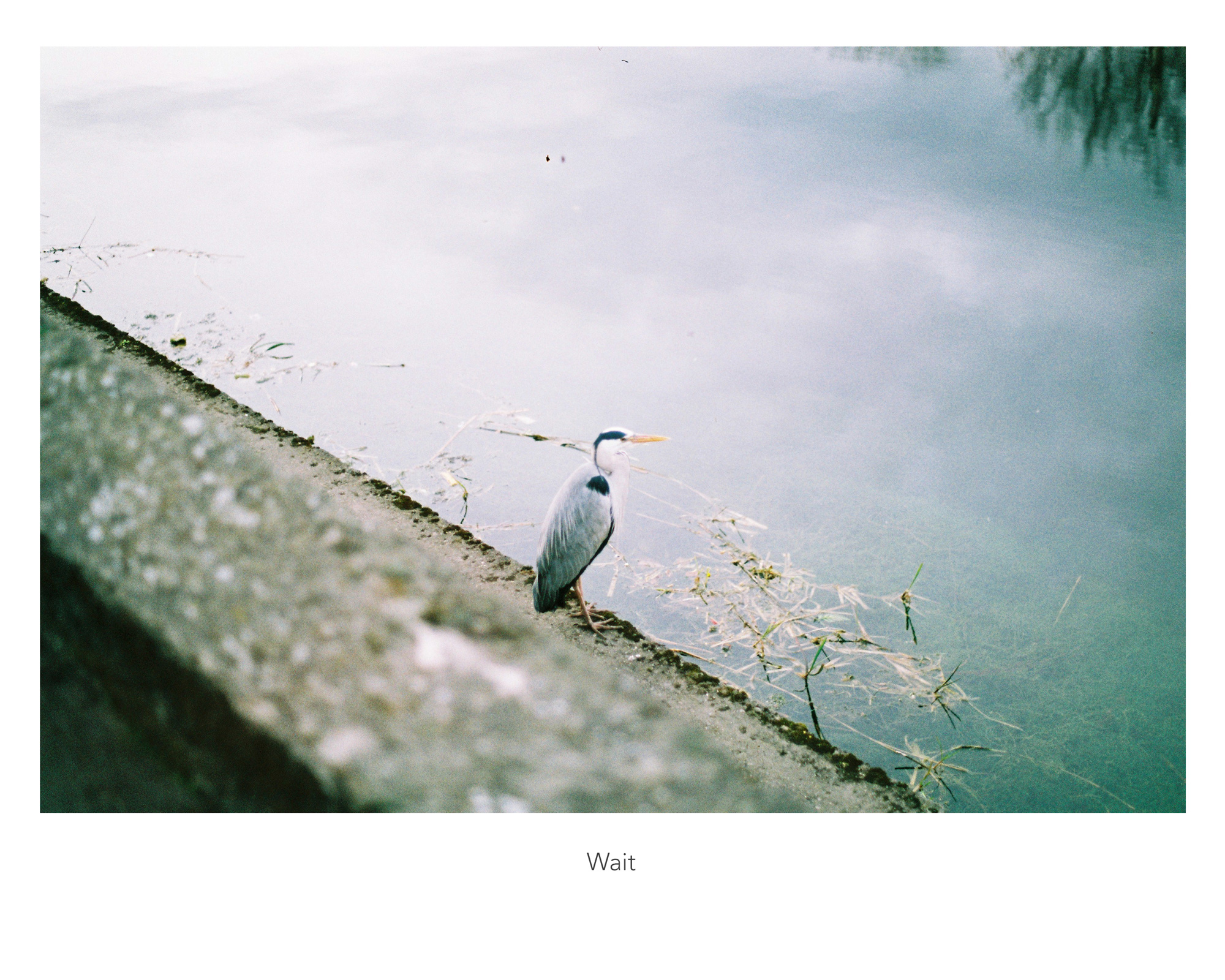

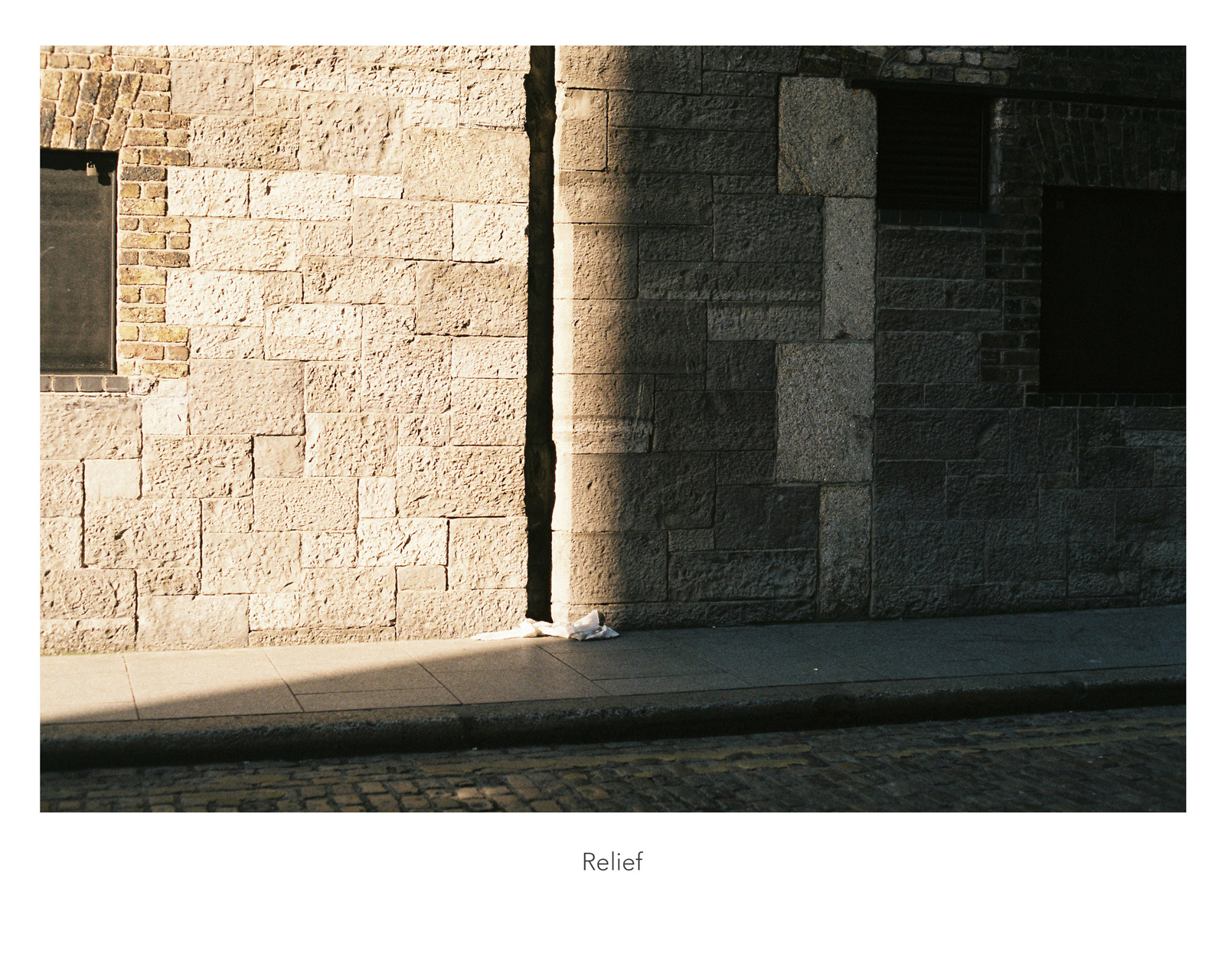

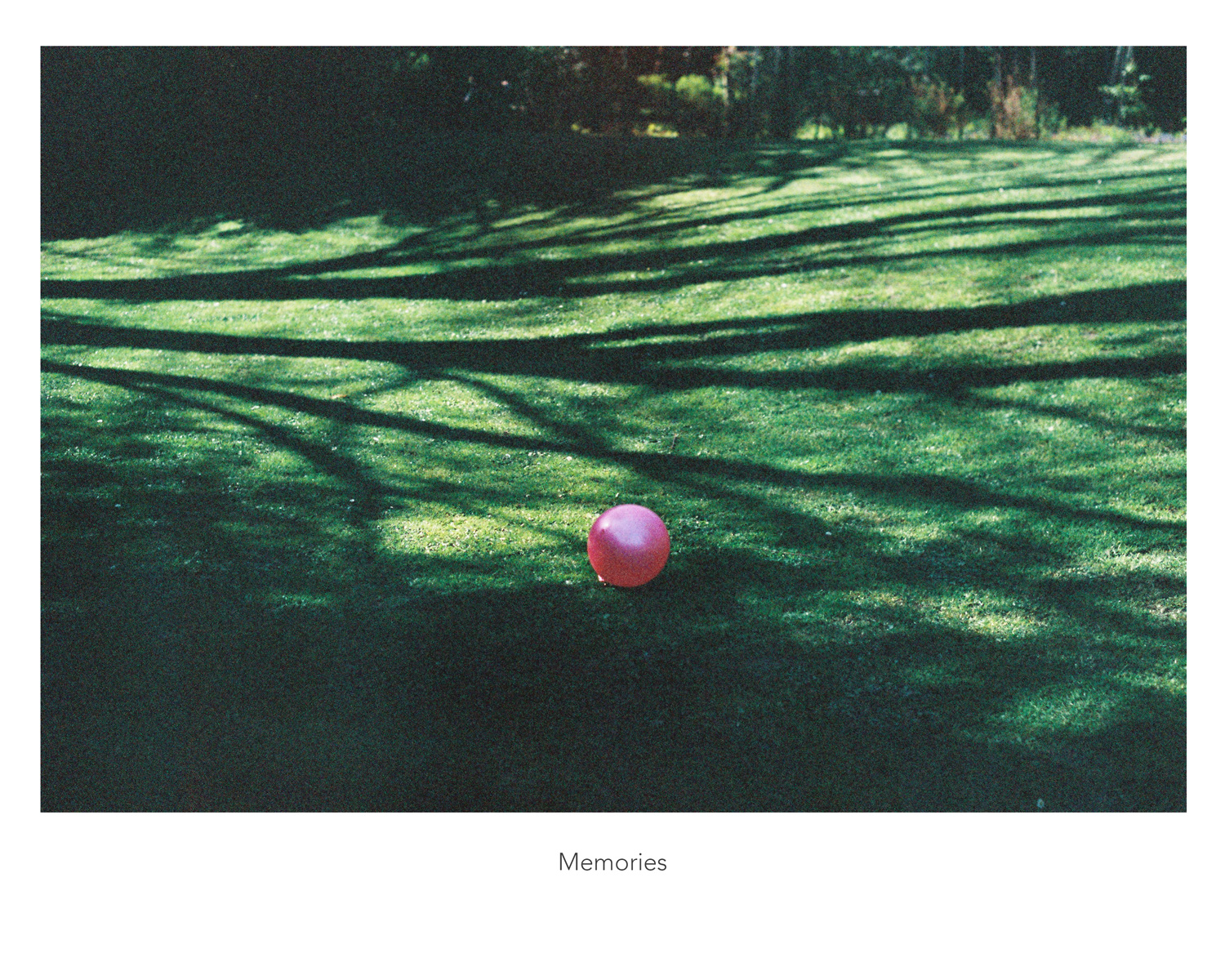

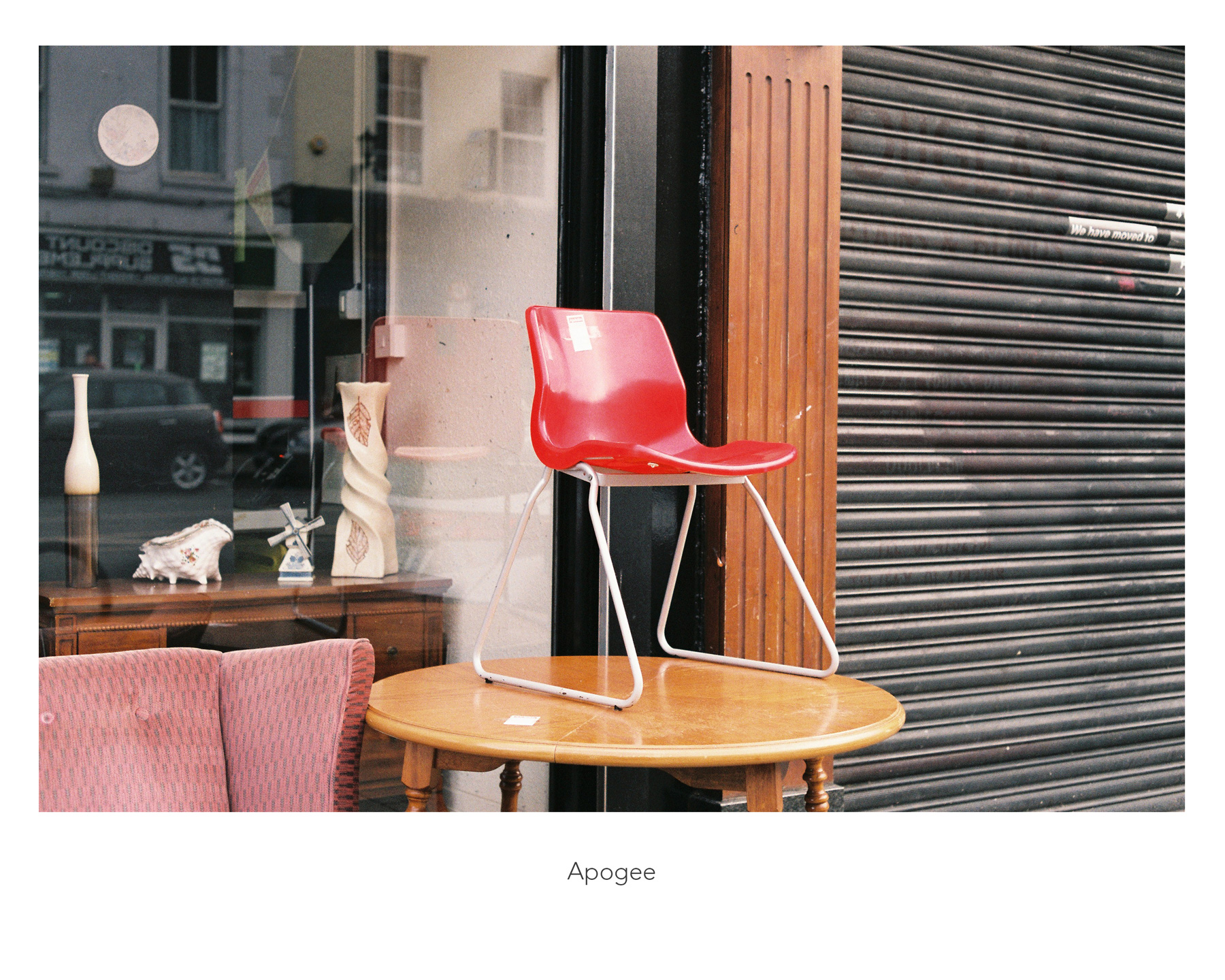

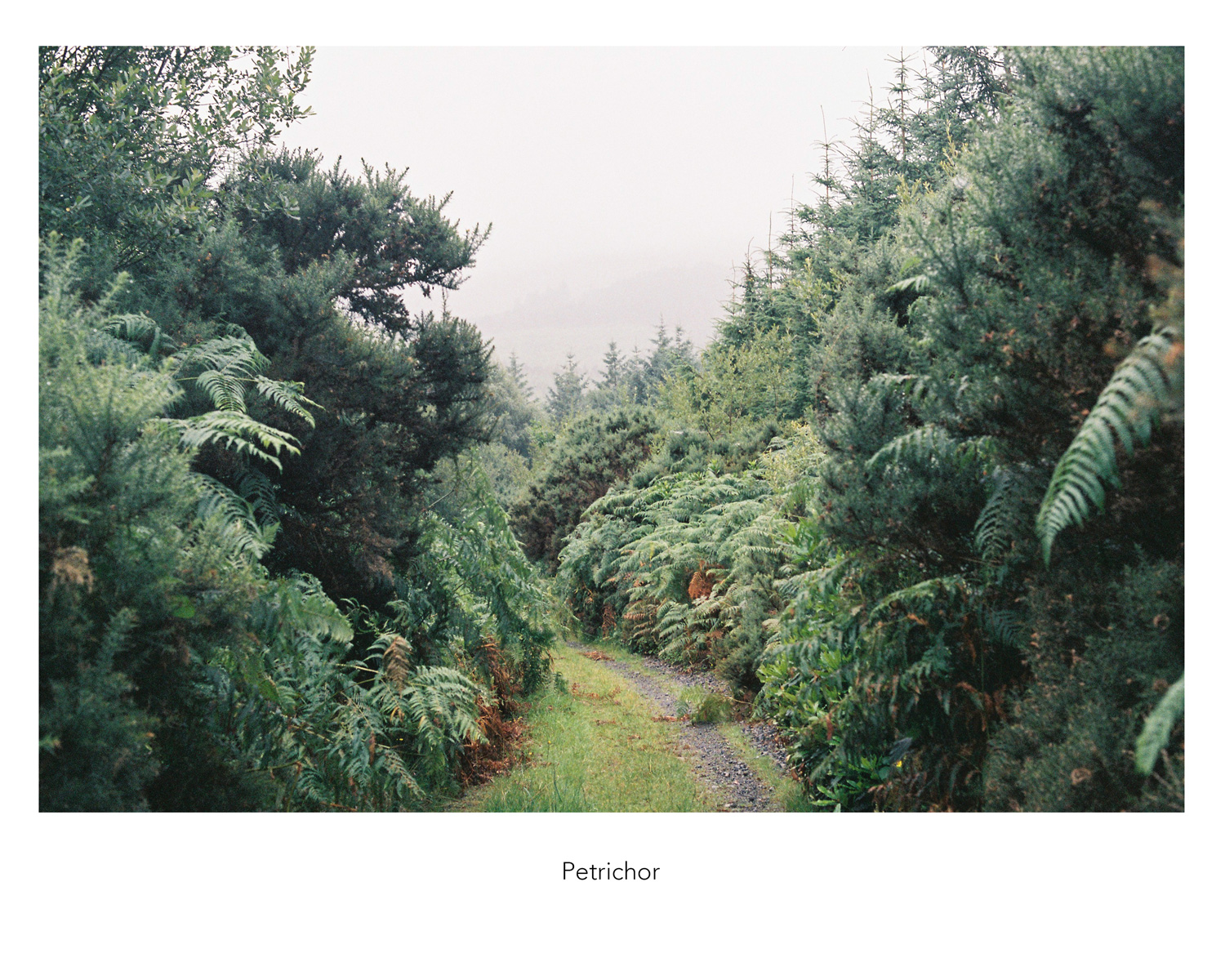

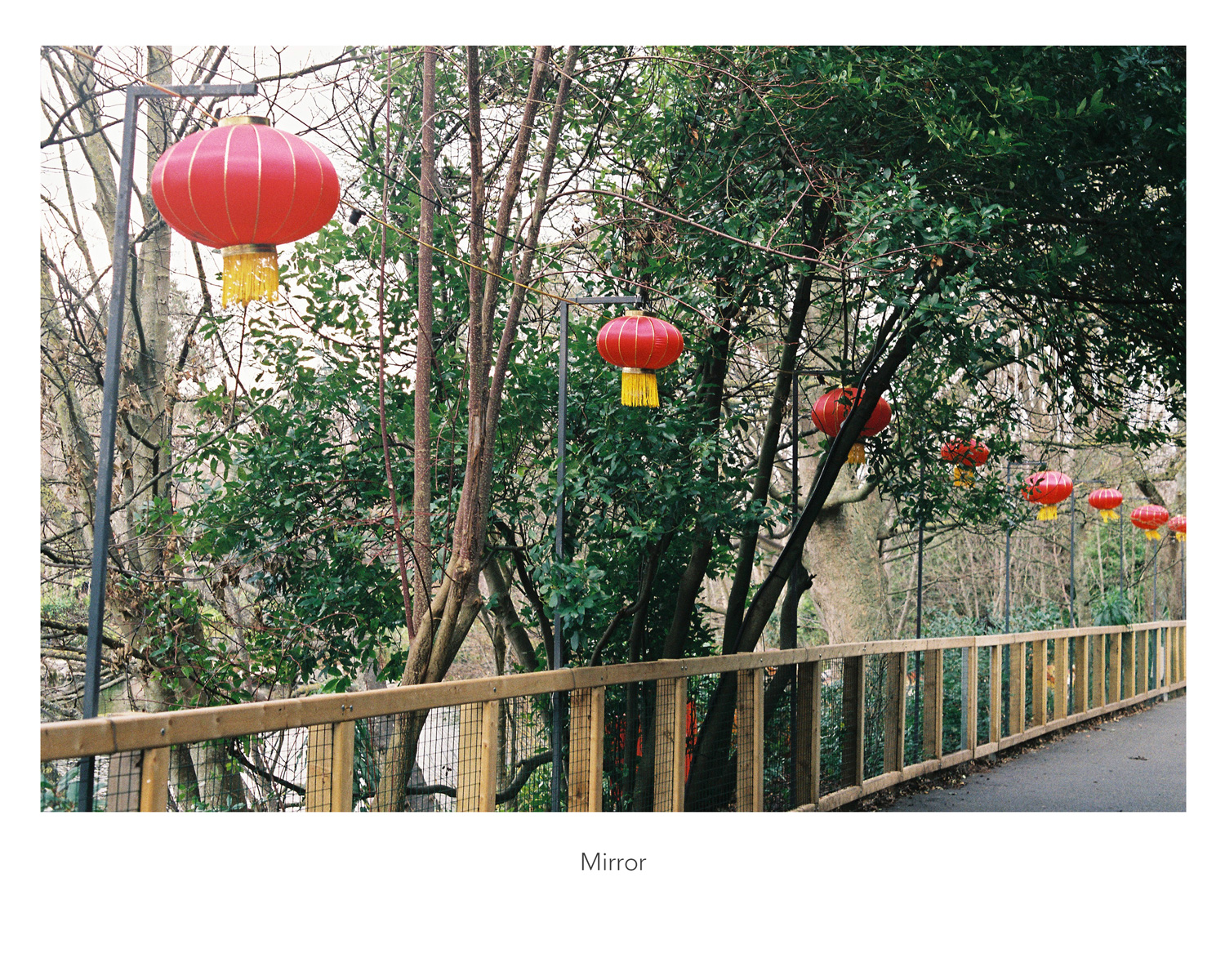

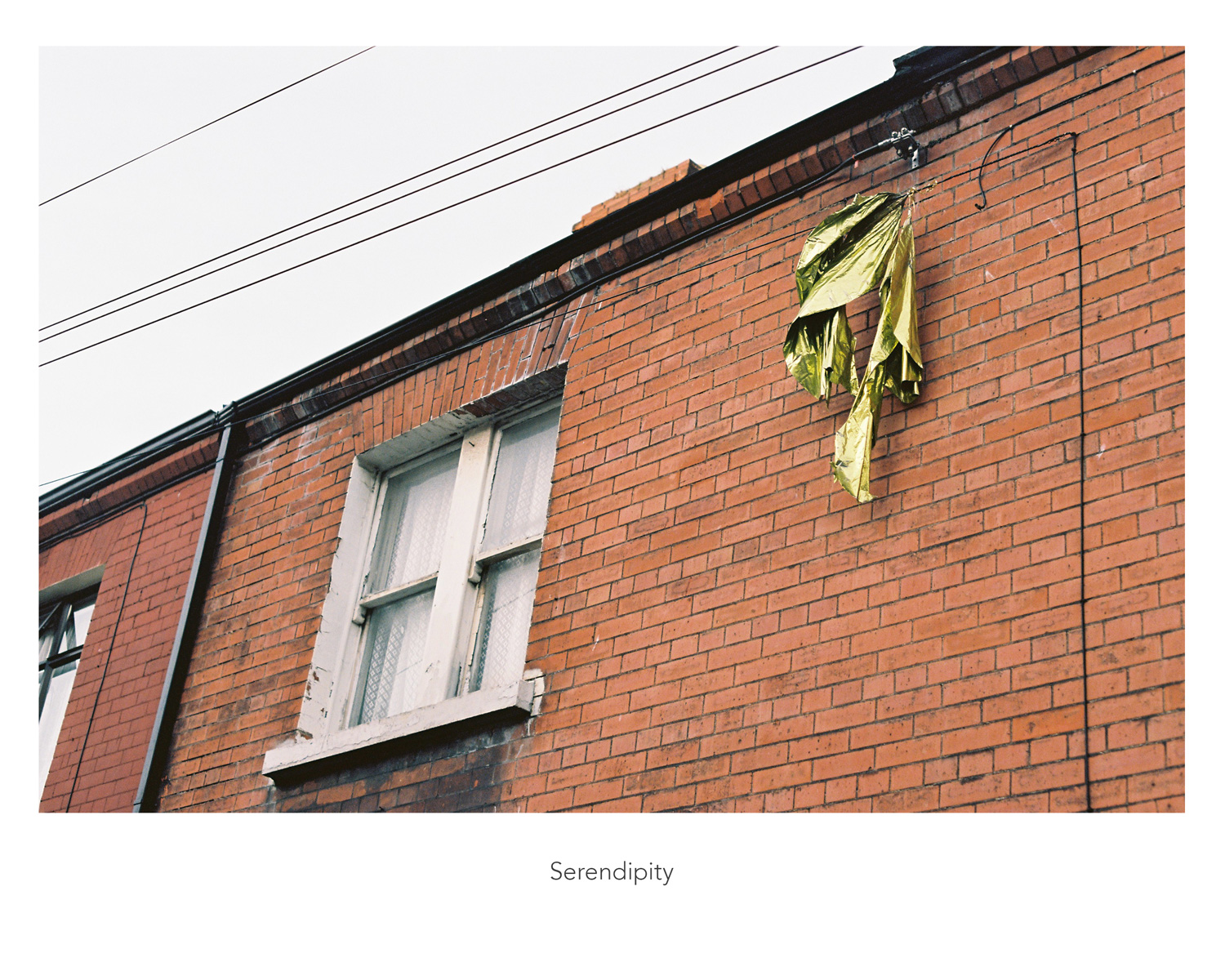

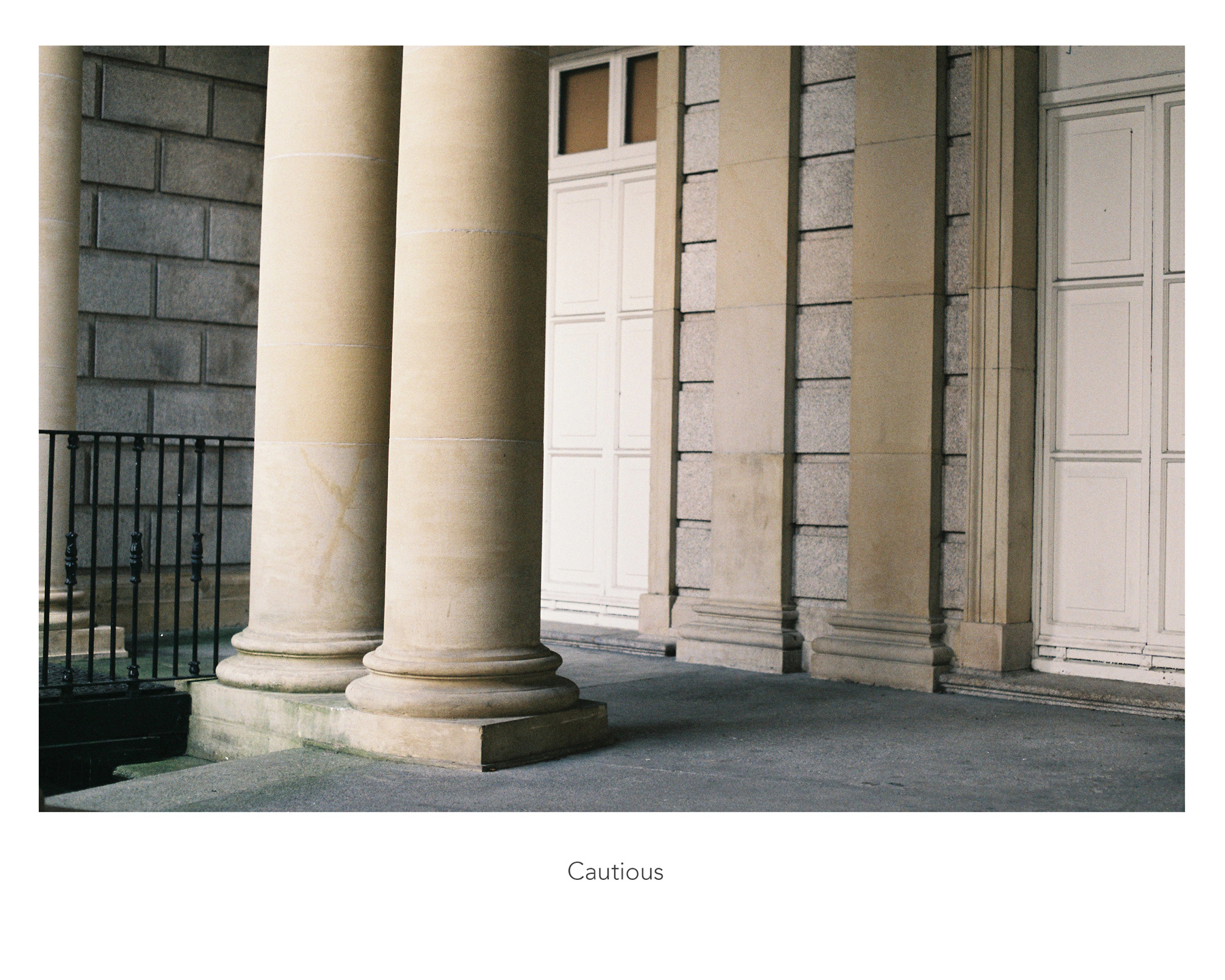

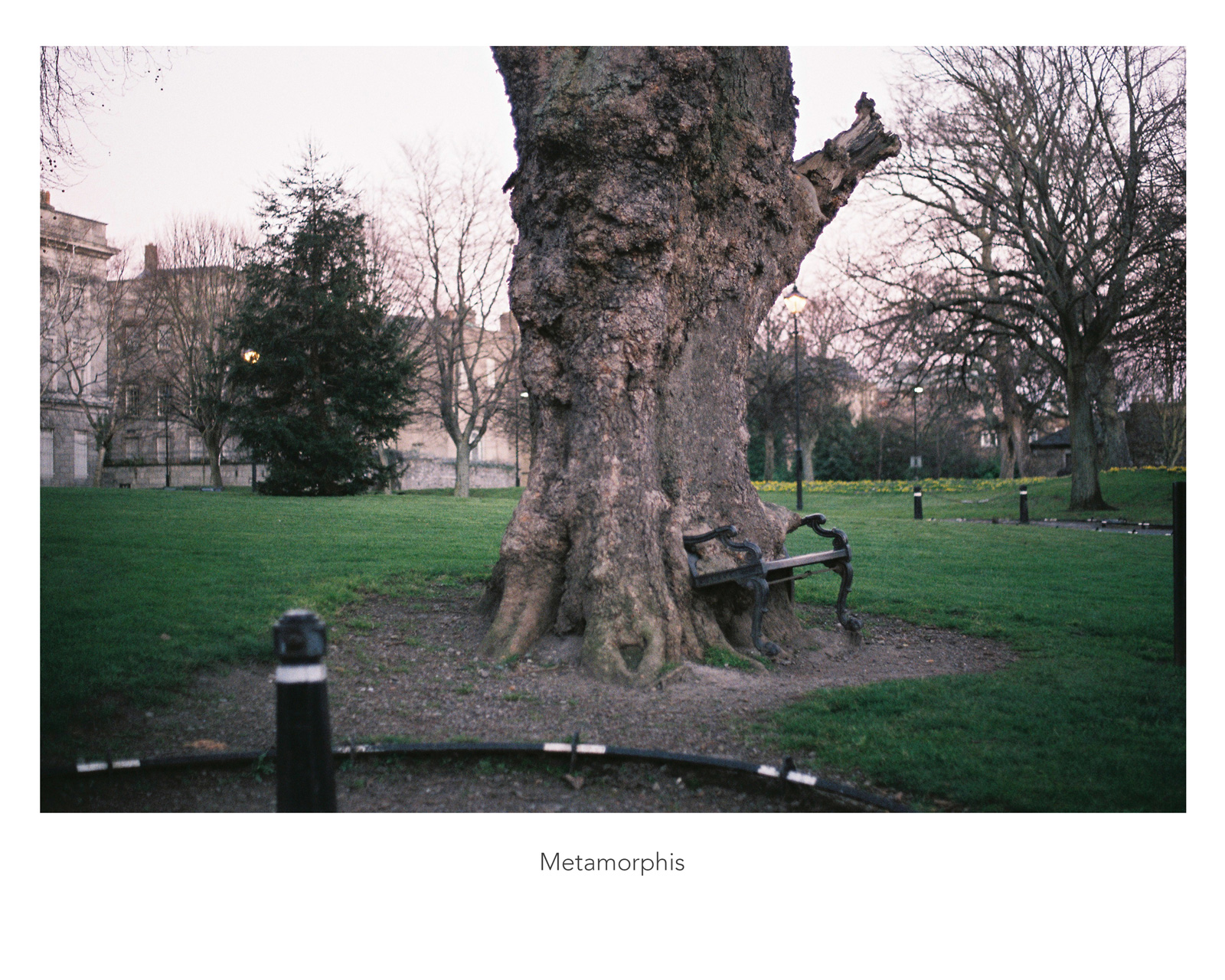

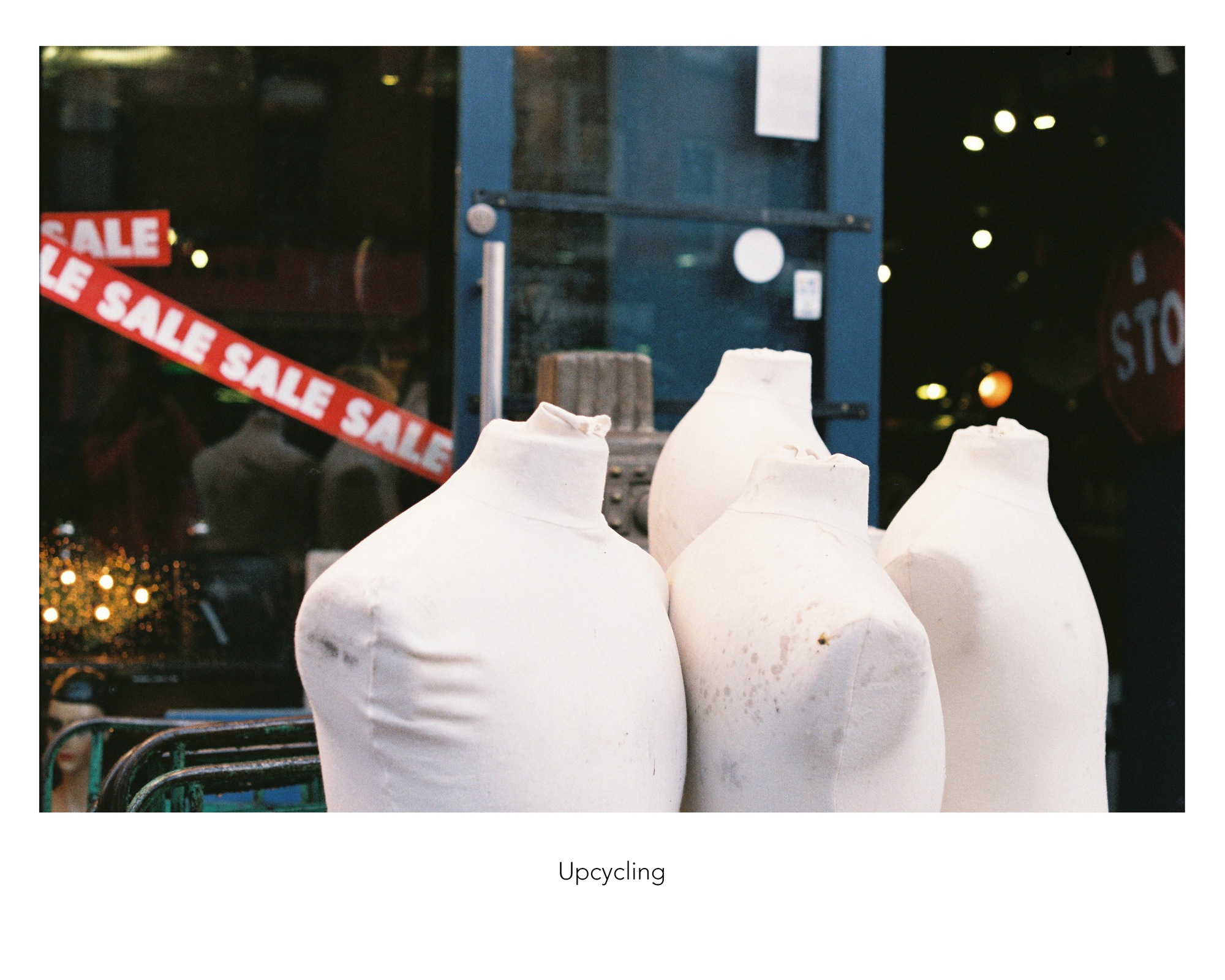

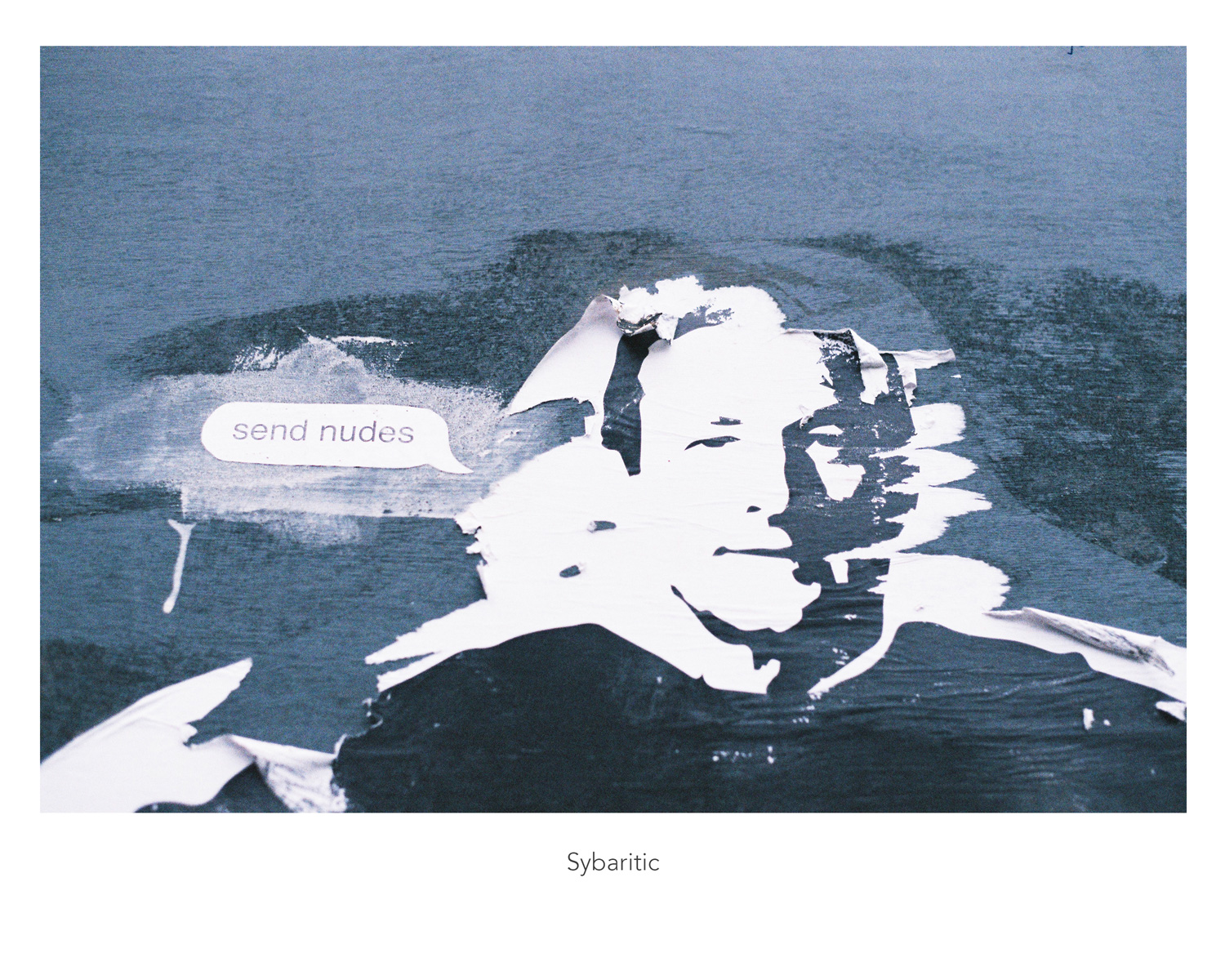

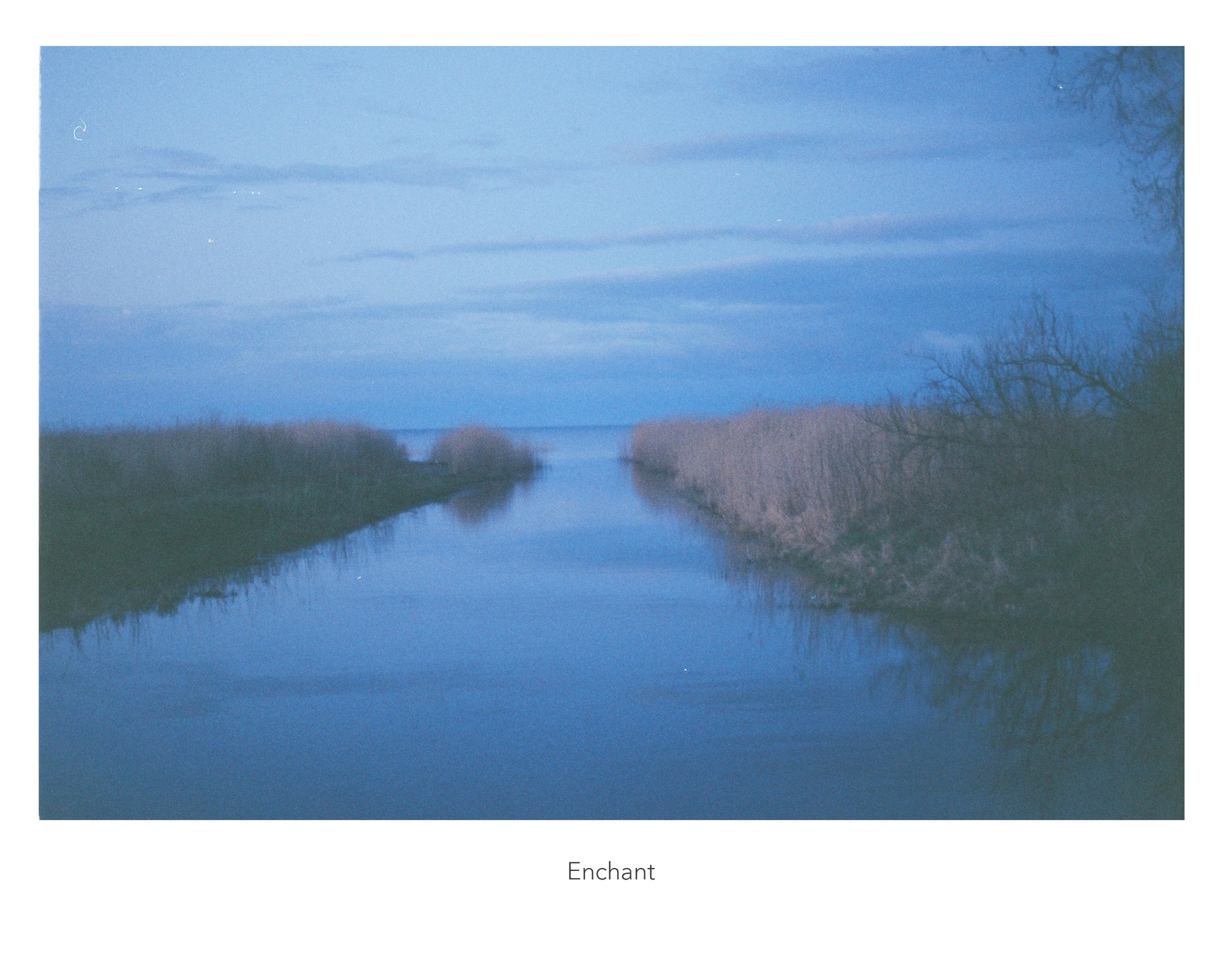

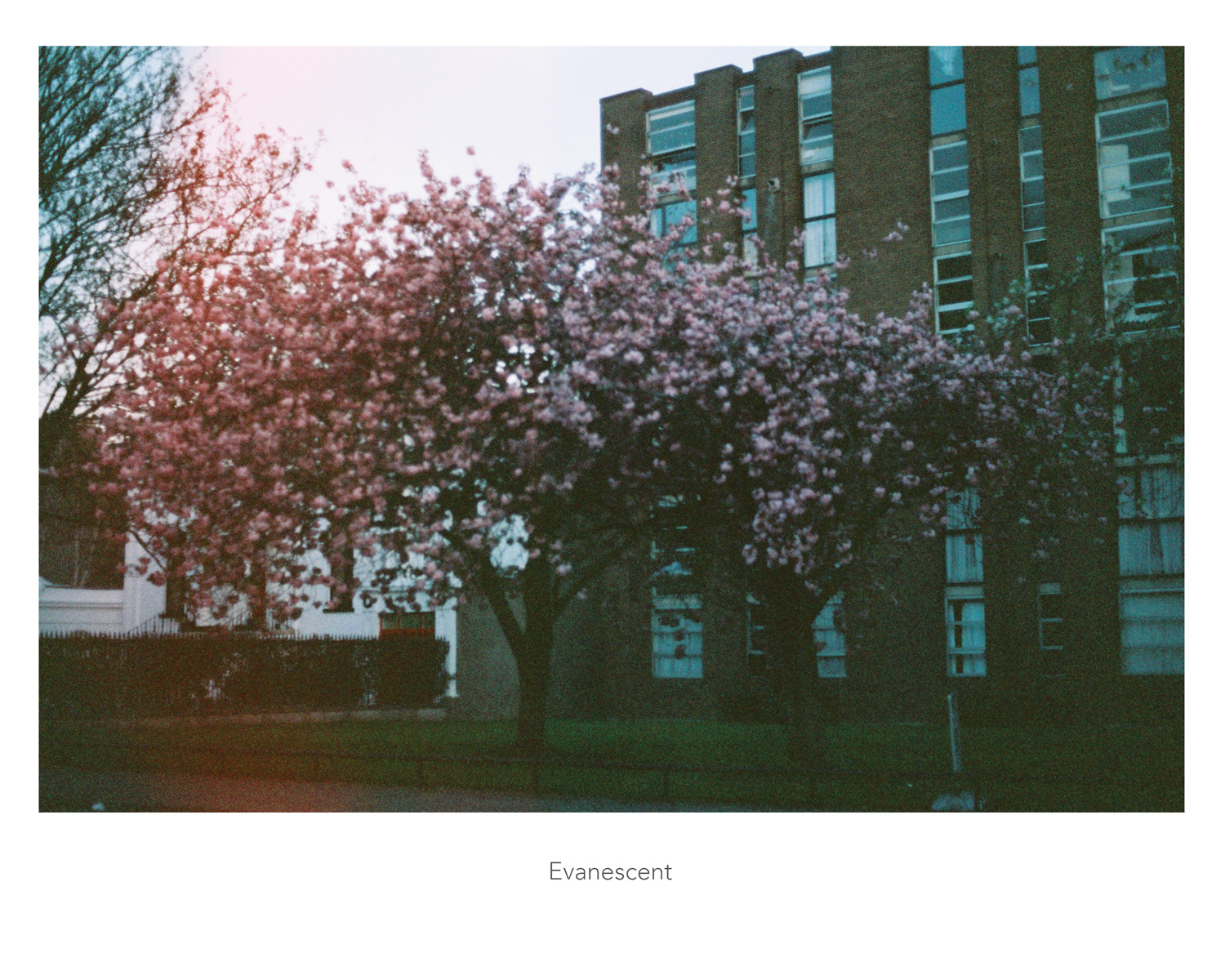

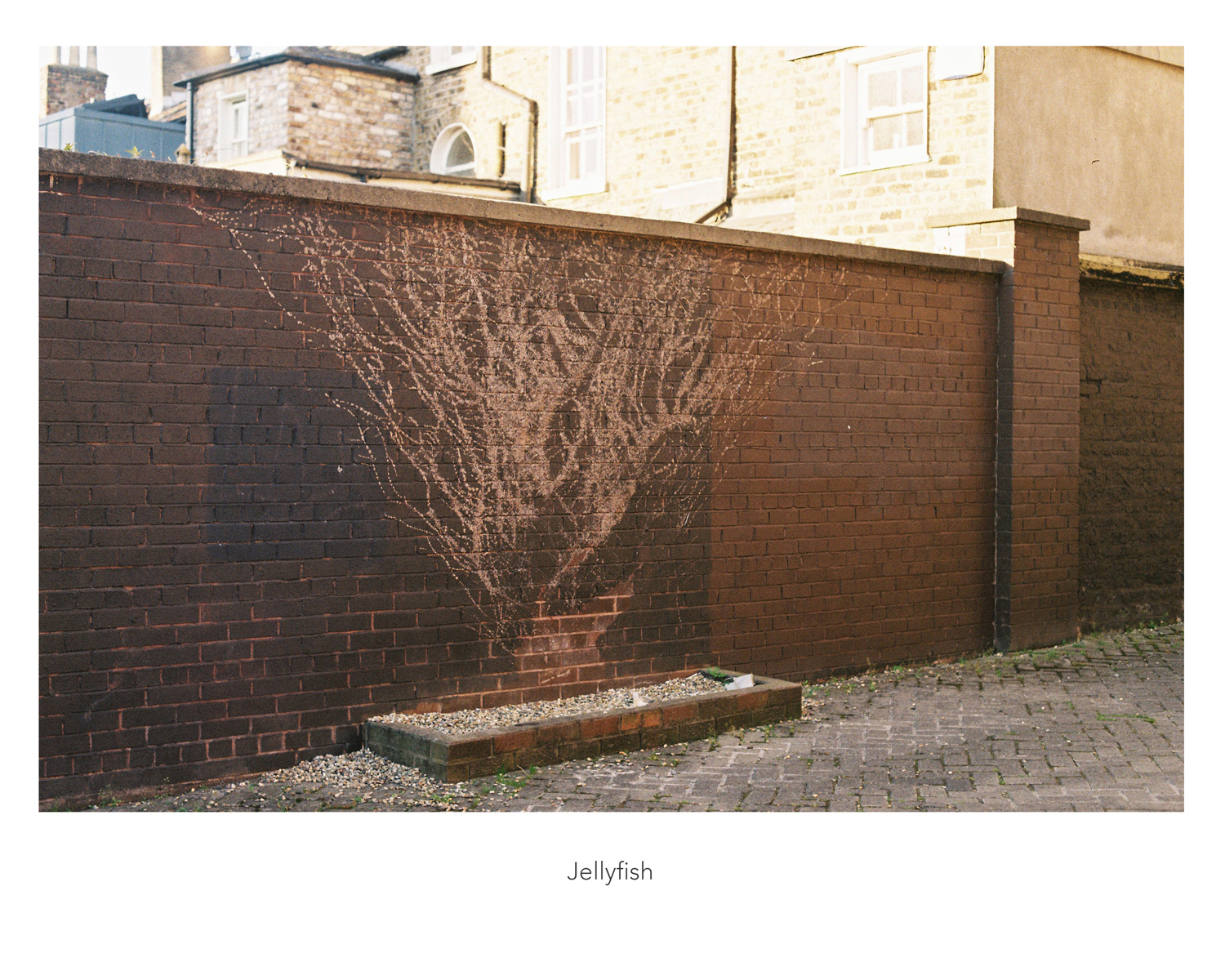

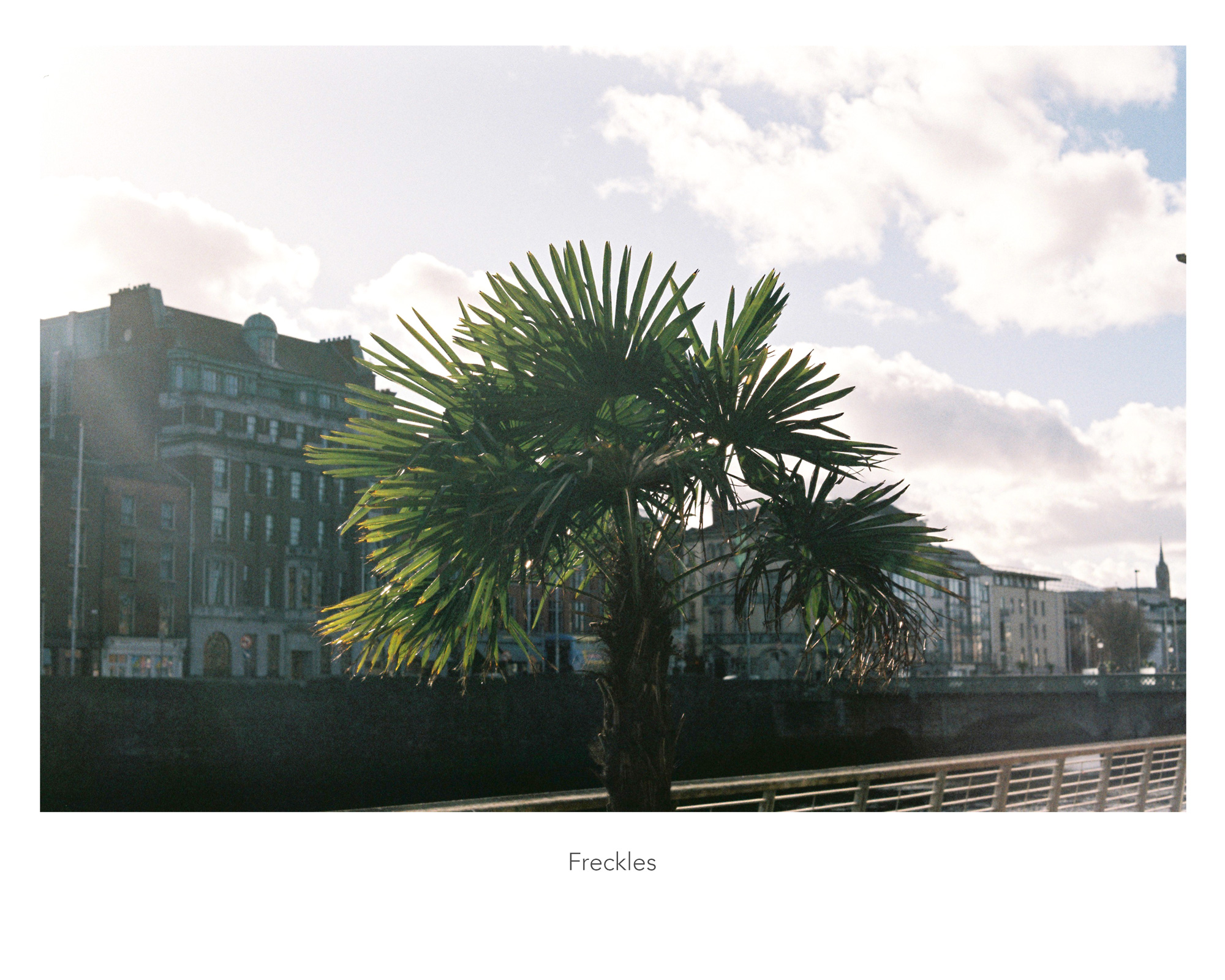

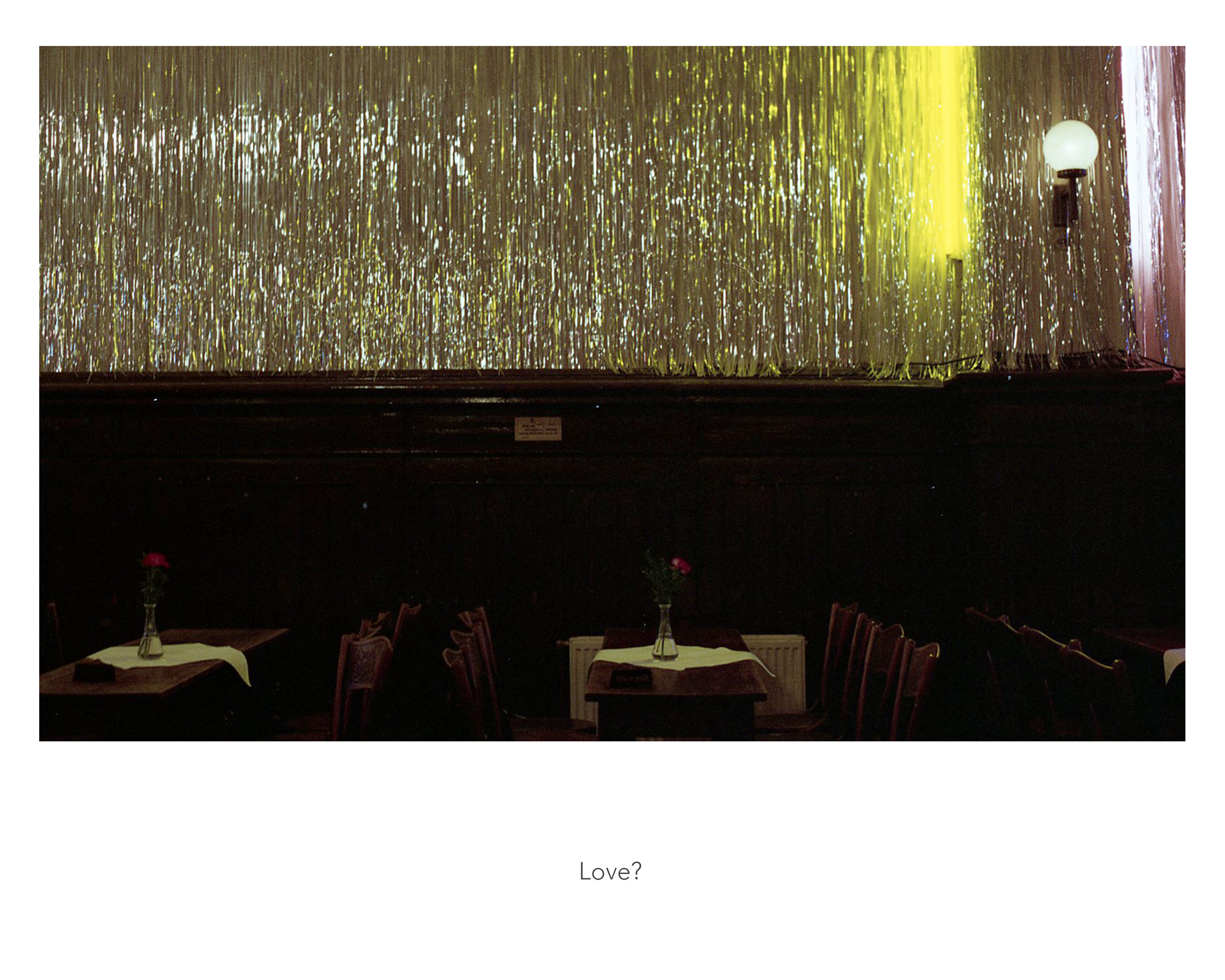

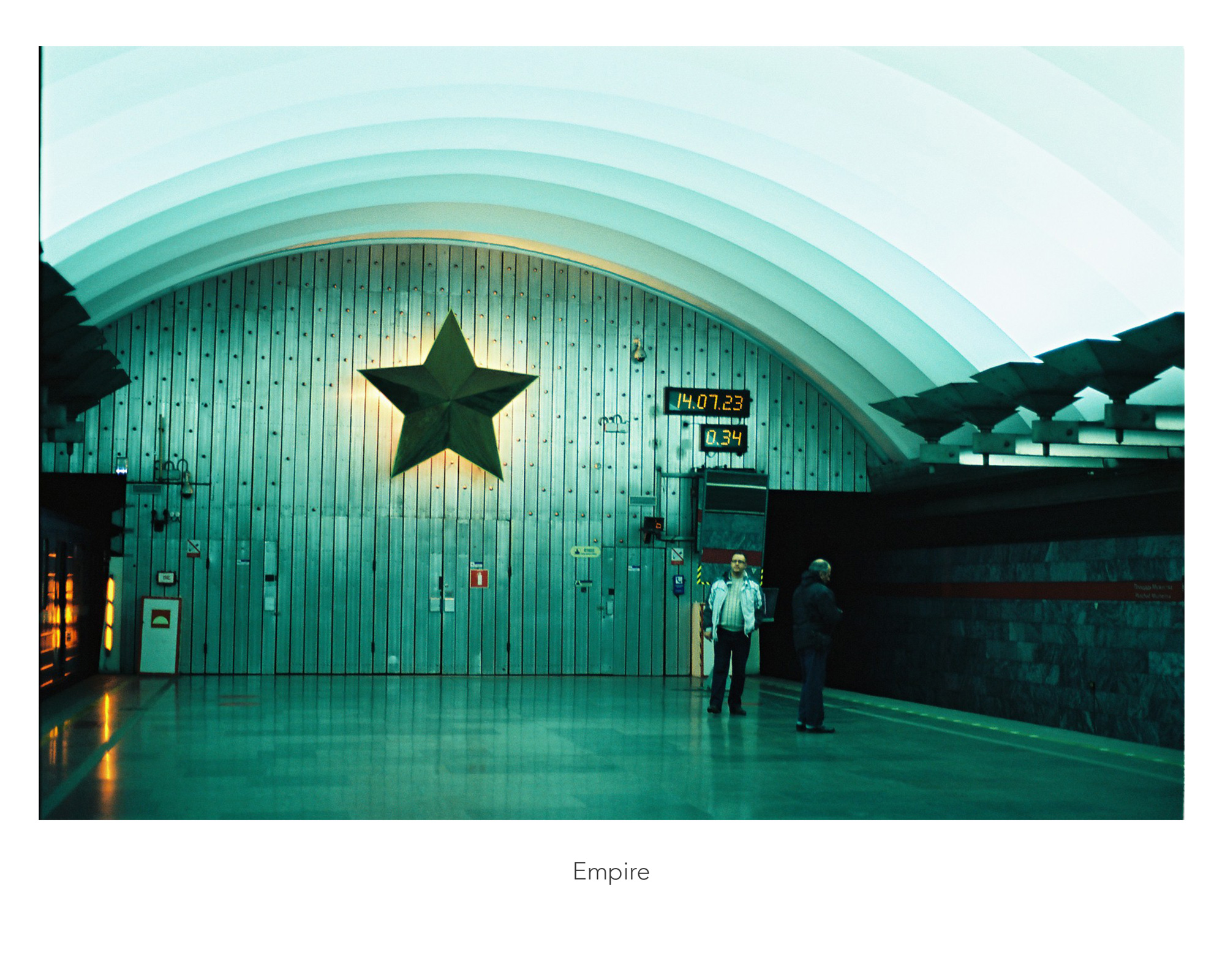

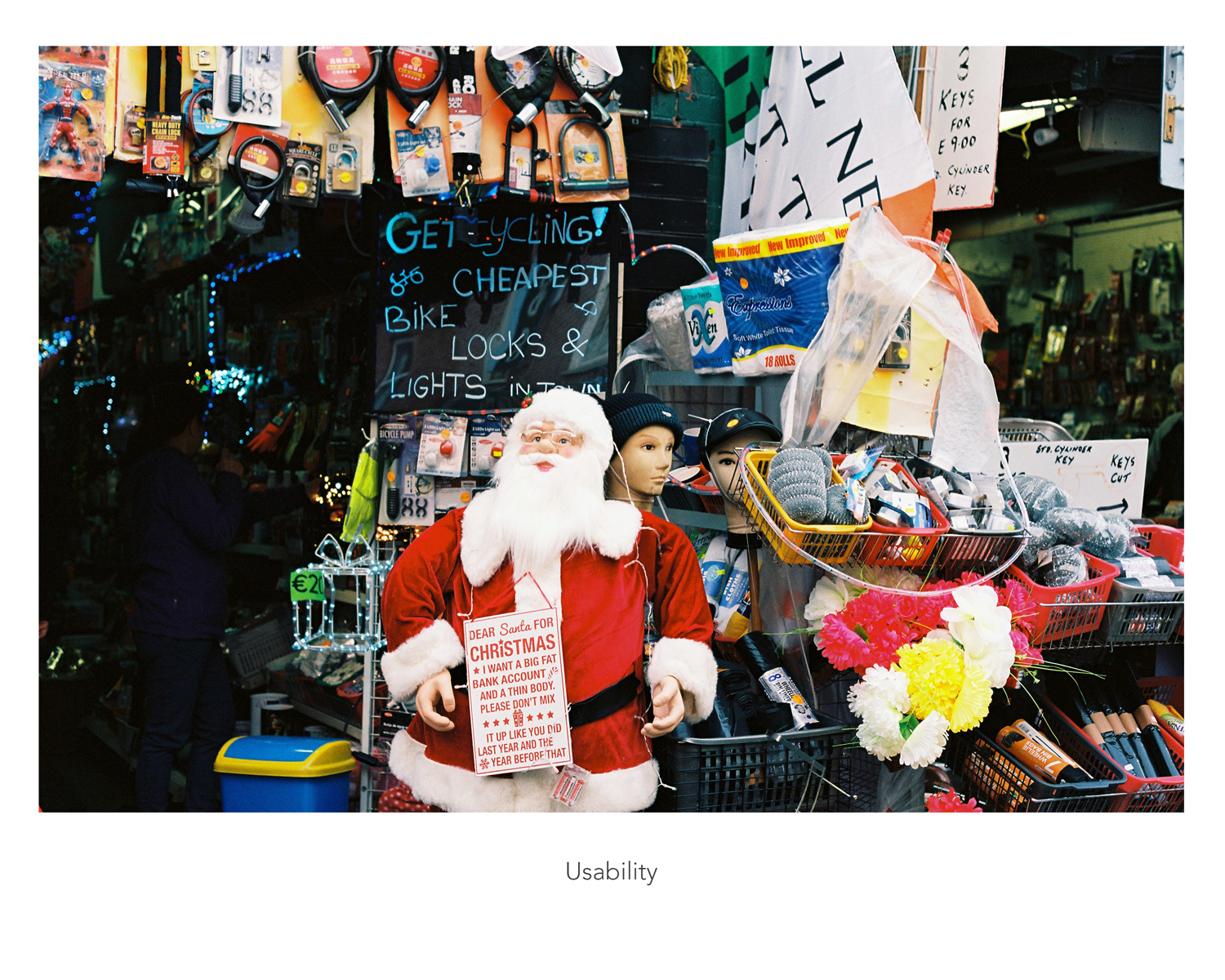

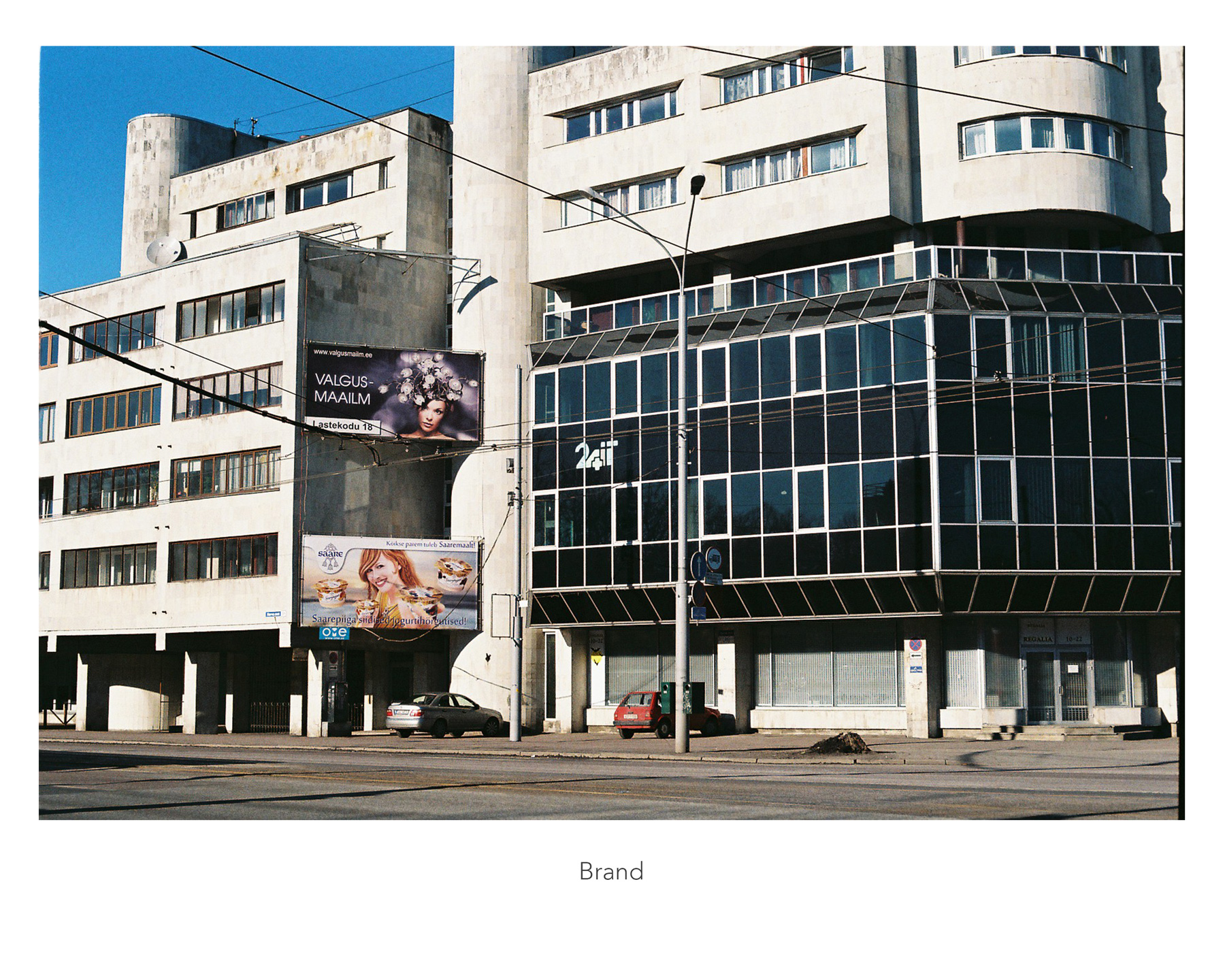

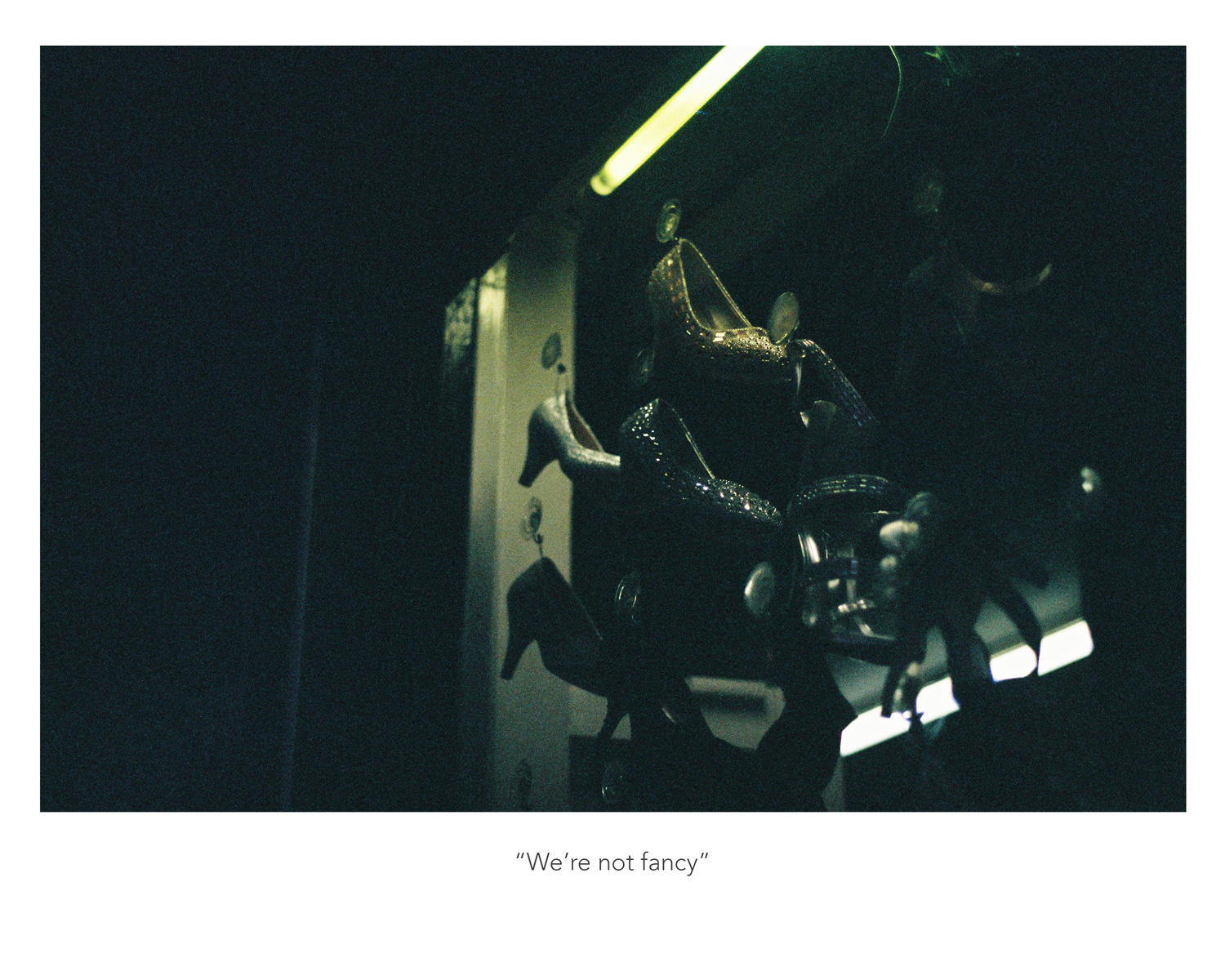

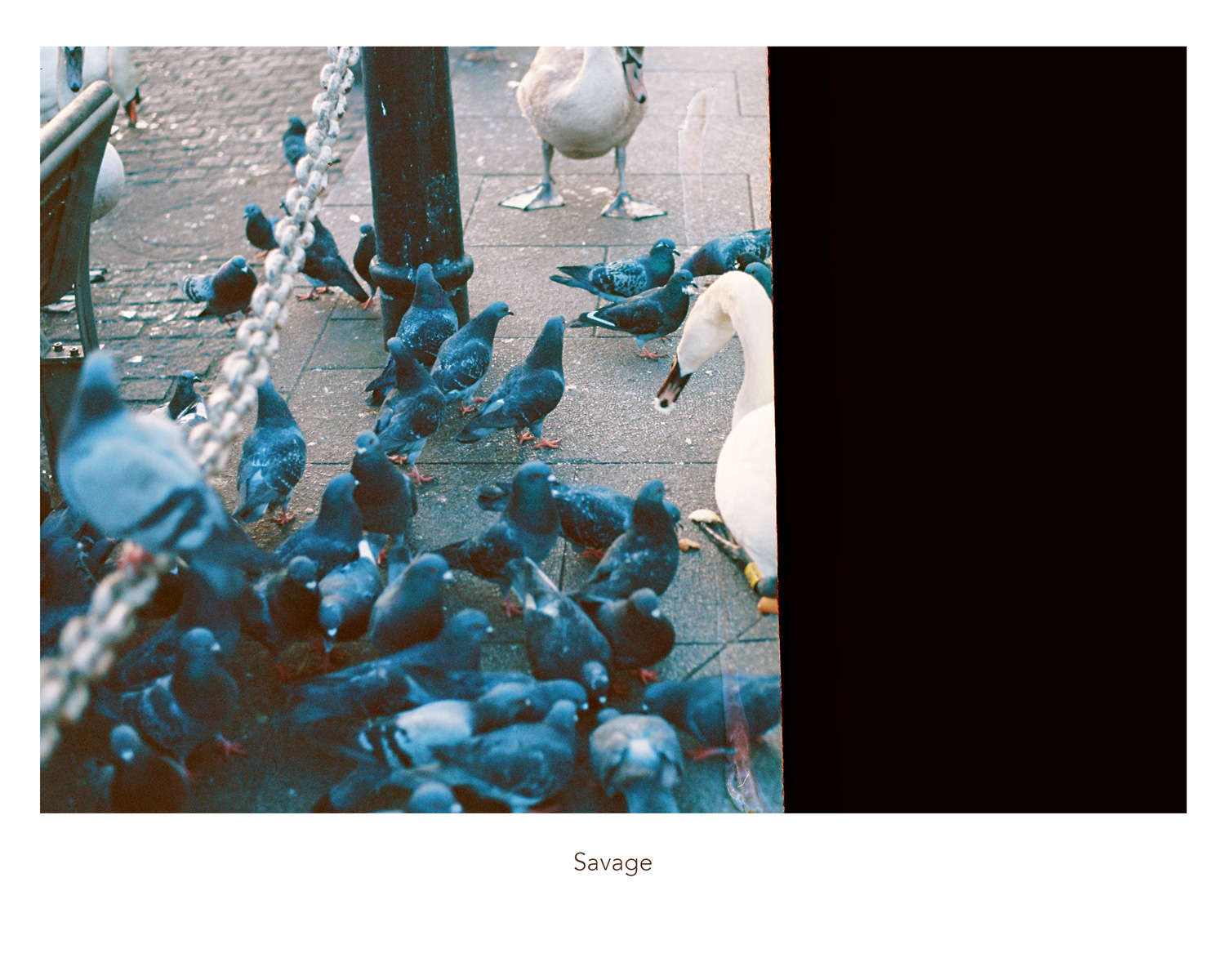

Below are the 40+ images that were responses to words sent to me. This small project is called Connection.

"YOU SEND ME A WORD, AND I SEND YOU A PHOTOGRAPH"

"You send me a word, and I send you a photograph"

This project originally started two years ago when I put out a request for people to send me words, and in return I would send them an image. The project had to be put aside for a while, and I never managed to get back to it.

I then recently had an unexpected few months living in Dublin, and I looked for a playful way to reengage with photography. Finding the old list of words, I went wandering.